|

1 | 2 |

3 | 4 |

5 | 6 |

7 | 8 |

9 | 10 |

11 | 12 |

13 | 14

|

ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AND LAW

|

Back

to Session 8: Protecting Natural Resources:

Endangered Species Act Part II

Controversies

While there are many controversial

issues associated with the ESA, we will focus upon two: (1) Fire Plan Protection

and (2) Property Rights.

Special Rules for

National Fire Plan Consultation

"In

December, 2003, several federal agencies jointly enacted

regulations designed to streamline the consultation process on

proposed projects that support the National Fire Plan. This

alternative consultation process eliminates the need to conduct

informal consultation with USFWS and NMFS for National Fire Plan

projects. Under the new process, the USFWS or NMFS will develop

an Alternative Consultation Agreement (ACA) with action agencies

(Forest Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land

Management and National Park Service). With an agreement in

place, USFWS or NMFS will train the agencies to make independent

determinations of whether their fire plan projects are likely to

adversely affect protected species. Projects might include

prescribed fire, thinning and removal of fuels, emergency

stabilization, burned area rehabilitation, road maintenance and

ecosystem restoration. This process is designed to accelerate

the rate at which the agencies process fire projects without

changing the actual standards for Section 7 consultations.

Alternative Conservation Agreements must include:

-

Who will make determinations;

-

Procedures for training to make

determinations;

-

Standards for assessing the effects of a

project;

-

Provisions for incorporating new information,

species, or critical habitat into the analysis;

-

Monitoring and periodic program evaluation;

and

-

Provisions for the action agency to maintain

a list of Fire Plan Projects for which it has made

determinations.

Critics of

this exception contend that the ESA requires at least informal

consultation and do not believe that the land management

agencies will have the expertise—despite the promise of

training—to make the proper determinations alone. Even assuming

the agencies have sufficient expertise, critics fear that the

conflicting missions of the agencies will lead to decisions less

protective of species and their critical habitats. A coalition

of environmental groups is challenging the new regulations in

court. For a copy of the new regulation and the agencies'

justification of it, see

Joint

Counterpart Endangered Species Act Section 7 Consultation

Regulations in the Federal Register.

For a copy of the ACA, see

the USFWS

web page on consultation.

For other USFWS recommendations for streamlining Section 7

consultation, see

the agency's

memorandum on Alternative Approaches to Section 7."

Property Rights and the

ESA

The history of the ESA

as it relates to property rights has been summarized by the

Congressional Research Service in the following fashion:

"Though Congress

first adopted endangered-species legislation in 1966, the

property-rights issue did not emerge until 1973 when it

enacted the ESA. The ESA considerably broadened federal

management authority over endangered and threatened species,

including those on private land.

Under the modern

act, the possibility of property-rights conflicts begins

when the Secretary of the Interior, through the Fish and

Wildlife Service (FWS), formally lists a species as

endangered or threatened. (The Secretary of Commerce,

through the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS),

administers the act for marine species.) Any species or

subspecies of fish, wildlife, or plants may be listed, and

separate populations of vertebrate species as well.

Significant here, listing is to be done "solely on the basis

of the best scientific and commercial data" -- i.e.,

without reference to property rights impacts.

Along with the

listing determination, the appropriate Secretary is required

when possible to designate the "critical habitat" of the

species -- areas essential to the conservation of the

species that may require special management or protection.

In sharp contrast with listings, a critical habitat

designation is to be based both on scientific data

and "economic impact and any other relevant impact" --

presumably allowing impacts on property rights to be

weighed. Indeed, the Secretary may even exclude an area from

critical habitat if the benefits of exclusion outweigh those

of inclusion (unless exclusion for this reason will cause

species extinction). This ESA distinction between listing

and habitat designation, allowing property-impacts analysis

only with the latter, was made by Congress quite

deliberately.

Of course,

species listing and habitat designation by themselves

occasion no direct interference with private property.

Rather, it is the ESA provisions triggered by these events

that may do so.

One such

provision, section 9, lays out prohibited acts in

connection with endangered animals and plants. Section 9's

prohibitions apply to private as well as public property,

and apply regardless of whether critical habitat is

involved. For endangered animals, prohibited acts include

(a) the "taking" of any such species, (b) possessing,

selling, or transporting any such animal obtained by

unlawful "take," (c) transporting an animal interstate in

the course of commercial activity, and (d) selling an animal

interstate, or importing/exporting same. For endangered

plants, the list is narrower, deleting the general "taking"

prohibition. The term "take," a key ESA concept not to be

confused with fifth-amendment takings, is generously defined

to include almost any act adversely affecting a species --

including "to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, ... capture, or

collect" a listed animal. Exceptions from section-9

prohibitions, aimed at accommodation of economic pressures,

may be authorized chiefly for "takings" incidental to

otherwise lawful activities, and undue economic hardship due

to contracts made prior to federal consideration of a

species as possibly endangered.

By general rule,

the FWS has extended almost all the above prohibitions to

threatened animals and plants as well. "Special rules"

have been promulgated for those threatened species having

atypical management needs, and for "experimental

populations."

The other ESA

provision with property-rights implications, section 7, sets

out federal agency obligations. Its sweeping

mandate is that each federal agency "insure" that its

actions are "not likely to jeopardize the continued

existence of any endangered species or threatened species,"

or harm designated critical habitat. The only exemption to

accommodate development is by action of the Endangered

Species Committee (popularly dubbed the "God Squad"), a

time-consuming and easily politicized process used to

completion only three times since it was established in

1977.

Stepping back,

one can readily see that the ESA is neither absolutist in

the protections afforded covered species, nor at the other

extreme sensitive to every property impact of those

protections. For example, the "incidental take" exception

was added to the ESA in 1982 precisely to soften the

private-property impacts of the act -- yet, on the other

hand, its availability is far from universal. By definition,

the "taking" can be excused only if it is incidental to, and

not the purpose of, the landowner's proposed activity, and

an incidental-"take" permit may be issued only when the

landowner has submitted a "habitat conservation plan," an

expensive proposition for some small landowners. This and

other private-property escape valves in the ESA are

discussed in more detail below.

According to an

analysis in 1993 by the Congressional Research Service, there

are three principal property-related impacts that may ensue from the

ESA:

"The first

type of possible impact occurs when the ESA

directly bars an activity on private land because it might

adversely affect an endangered or threatened species.

ESA section 9 bans the "taking" of a listed species, a term

that includes significant habitat modification -- even on

private land. On the other hand, the act seeks to

accommodate economic pressure by allowing "takes" of listed

species that are merely incidental to a proposed activity.

ESA section 7 orders federal agencies to insure that their

actions, including permitting, are unlikely to jeopardize

the continued existence of a listed species. Like section 9,

section 7 allows incidental "takes," and can be bypassed

entirely by action of an Endangered Species Committee. While

the possibility of direct land-use prohibitions under the

ESA sparks most of the congressional debate, there appears

to be not a single constitutional taking decision from the

courts based on such restrictions.

The second

type of theoretical impact occurs when the ESA

limits one's ability to protect property from the

depredations of listed species. ESA section 9

contains no defense for protection of private property,

though importantly, "special rules" allow government agents

to deal with nuisance animals. One ESA case has been decided

in this category, finding no constitutional taking, and most

non-ESA depredation cases have yielded the same result.

Instances where the protected species exists on private land

through government relocation, however, may offer better

prospects for the taking plaintiff.

The third

type of possible impact occurs when the ESA

limits commercial dealings in members of species that were

acquired before the species was listed. ESA section

9 contains the pertinent language. Supreme Court taking

decisions suggest that constitutional relief in these

circumstances is particularly unlikely. A key reason why

courts are not finding constitutional takings is because

until now they have deemed the restrictions in wildlife

statutes to be land-use controls, rather than to effect

permanent physical occupations by the protected animals. The

former type of government interference with property is more

rarely held to be a taking than the latter. For this and

other reasons (but stressing the difficulty of prediction in

this area), it seems that few ESA impacts on private

property are likely to be constitutionally compensable."

In recent years,

some of the most significant critiques of the ESA have come from

a group that is very intimately associated with its

inner-workings: The

National Governors Association. In 2004, this group provided

the following critique of the limitations of the act and

proffered a set of recommendations.

"Reviewing the

record of the last thirty years, the Governors make the

following observations.

-

Funding for

ESA should be enhanced to address the growing list of

threatened and endangered species. Significant funding

needs to escalate rapidly, as state and federal agencies

increasingly assume ESA management activities and

embrace ecosystem management strategies as means to

protect species and their habitats.

-

ESA would

benefit from providing more meaningful opportunities for

states to comment, participate, or take the lead before

the federal government makes any number of

decisions--ranging from listing through delisting--under

ESA. Such consultation is largely optional under the

current scheme and has been provided erratically. The

role of states also has been limited by rigid internal

federal processes, interagency jurisdictional disputes,

and interpretations of the provisions of the Federal

Advisory Committee Act (FACA). This scenario has

prevented the sharing of scientific information and the

consideration of state-based information.

Together, all of

these factors would help rebuild public support and

enthusiasm for the maintenance of biological diversity and

the protection of species and habitats. Public support is

essential to successful accomplishment of the goals of the

act as established by Congress.

Recommendations

The National

Governors Association calls for the reauthorization and

amendment of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 based on

three goals: to increase the role of states, to streamline

the act, and to increase certainty and technical assistance

for landowners and water users. These goals should be

achieved while maintaining the act's integrity and original

intent to conserve listed species. Implementation of the

following recommendations will improve the effectiveness of

the act by making it more workable and understandable.

Multispecies

Planning. Increasingly, state and federal agencies and

private conservation organizations have recognized the

limitations of the "single-species approach" to conservation

and have taken commendable steps to utilize Section 4(d)

rules and habitat conservation plans to move toward

multispecies planning. The act should authorize the recovery

and protection of species in clusters or related groups,

where appropriate. It should continue to give priority to

the conservation of the species and habitats that, if

protected, are most likely to reduce the need to list other

species dependent on the same ecosystem.

There is wide

agreement that the value of habitat-based planning lies not

only in its benefit to species and ecosystems, but also in

its promise of long-term certainty with respect to land use

both within and outside of designated critical habitats. A

planning process for multiple species should include

incentives such as authorization for short-form,

cost-effective habitat conservation plans under Section 10;

"no surprise" policies; safe-harbor policies; small

landowner and small impact exemptions; and other initiatives

that provide certainty and encourage voluntary efforts by

landowners.

State

Delegation and Increased State Role. The act should

affirm and be carried out in a manner that recognizes the

broad trustee and police powers that states possess over

fish and wildlife within their borders, including those

found on federal lands, and the concurrent jurisdiction for

listed species that the states and the U.S. Secretary of

Interior share. The act can be effectively implemented only

through a full partnership between the states and the

federal government.

One way to

accomplish this partnership is through the delegation of

authority for the development of conservation and recovery

plans by states that accept that delegation and agree with

the secretary to perform in accordance with specified

standards. A federal-state collaborative rulemaking process

should be established to determine the standards and

guidelines for state participation in or assumption of

authority for decisions under the act, while recognizing

that the secretary retains final decisionmaking authority.

Such delegation should be accompanied by grants to cover

additional administrative costs. If a state chooses not to

lead an activity, it should remain a full partner in

administering the federal program to ensure that its

authorities, on-the-ground expertise, and working

relationships with local governments and holders of real

property rights are utilized and that duplication is

minimized.

Public

Participation. To increase cooperation, the law must

enable stakeholders to participate directly in the important

decisions of ESA management. Currently, public comments are

only required to be solicited for the development of

recovery plans. During both the listing process and the

drafting of recovery plans, public hearings and the

solicitation of comments should be required and significant

comments should be addressed.

In addition,

current law allows judicial review only for the denial of a

listing petition, not for the acceptance. To ensure fair and

equal access to the legal system, judicial review must be

granted for both the denial or the acceptance of petitions.

As an

alternative to judicial review, ESA should incorporate

alternative dispute resolution mechanisms or mediation

activities as means to resolve disputes and ensure the best

application of scientific information in listing decisions.

Enhanced

Science. Given the broad implications that may arise

when ESA actions are taken, decisions must be based on good

science. Peer review of listing decisions by acknowledged

independent experts and/or state wildlife experts is

important to ensure the public that decisions are

well-reasoned and scientifically based.

Peer review

committees should be agreed upon by both the U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service and the state. State agencies also have

expertise and other institutional resources, such as mapping

capabilities, biological inventories, and other important

data, that should be employed in developing endangered

species listing and recovery decisions. FACA is an obstacle

that prevents the free flow of information between states

and federal agencies with wildlife management

responsibilities. As concurrent regulators, state government

agencies must be exempt from FACA restrictions.

Recovery

Goals. The act should have as its central focus the

recovery of species. Every effort should be made to complete

a recovery plan within one year of a species being listed,

and federal agencies should publish recovery goals in

conjunction with the listing decision based on the best

available science at the time of listing. Designation of

critical habitat should be discretionary if the secretary

determines it is either undeterminable or is not necessary

for the protection of the listed species. If critical

habitat is designated, the act should provide for such

designation during the development of recovery plans. An

administrative process to downlist and delist species should

be automatically triggered when the quantitative goals and

targets of a recovery plan are met. The secretary should be

given the flexibility to allow, to the maximum extent

practicable, species to be delisted or downlisted, along

state geographic boundaries, when they have reached their

recovery goals within a state, regional, national, or

multistate recovery program that has been developed

consistent with the purposes of the act.

Recovery plans

should provide expedited Section 7 consultation procedures

and inexpensive short-form, model habitat conservation plans

as incentives for participation, as well as special relief

for small landowner and small impact activities. Direct

stakeholder responsibility and participation in developing

the implementation plans that carry out recovery plans and

conservation agreements will reduce litigation and delay.

These improvements not only benefit the species, but also

benefit the affected locality. The public has a right to

know whether it will be impacted with the implementation of

ESA. For this reason, positive and negative economic impacts

must be assessed and considered in order to minimize adverse

impacts during the preparation of recovery plans.

Governors urge

the federal government to ensure states and their state

agency experts are included in the recovery teams that are

charged with the development, implementation, and management

of species recovery programs. State personnel bring

management expertise, local proficiency, and working

relationships with private landowners and local regulatory

agencies that need be involved in the recovery program.

Congressional

intent in the 1973 act to distinguish between endangered

species and threatened species has been almost entirely

eroded. Congress must reassert the distinction as originally

intended. When a species is classified as threatened,

regulatory restrictions appropriate to endangered species

must give way to greater deference to states, greater

program flexibility, and a broader range of permissible

actions in developing a creative conservation program.

Funding.

Inadequate funding remains an impediment to the success and

the public's support of ESA. Without adequate funding,

burdens are unfairly placed on local communities and owners

of private property. The Governors call for the formation of

a national task force composed of federal, state, and local

representatives to identify creative and equitable funding

strategies. Such a task force must have the stature to

generate meaningful recommendations that will overcome the

institutional inertia on ESA funding. Possible funding

sources to enhance the effectiveness of the act include the

Land and Water Conservation Fund, the original intent of

which was to provide at least 50 percent of proceeds to

state programs but which is now directed almost entirely to

federal agencies, and the Transportation Enhancement

Activities Program.

Incentives.

Although a majority of endangered and threatened species are

found on nonfederal land, there are few incentives for

private landowners and state and local governments to

undertake conservation measures before a crisis exists. The

reauthorized act must provide incentives for state and local

governments, private landowners, and private organizations

to assist in species habitat and species conservation and

with recovery efforts and habitat preservation. However,

these incentives should not replace or supercede the need to

fully fund existing ESA programs within the U.S. Department

of Interior and the U.S. Department of Commerce.

The Governors

recommend to Congress those incentives described in the

Keystone Center's Keystone Dialogue on Incentives to

Protect Endangered Species on Private Land (July 1995).

The Governors also endorse efforts to expand nonregulatory,

incentive-based, and commercial conservation efforts.

In addition,

states should be authorized to initiate conservation

agreements with federal, tribal, and local agencies and

private landowners to conserve declining species before the

need to list those species. In cooperation with the states,

the secretary should determine the standards and guidelines

for these conservation agreements. These agreements should

include landowner certainty provisions and incentives to

encourage the involvement of federal agencies as well as

private landowners and other nonfederal parties in this

preventive effort."

Utilitarian Calculations of Value of Endangered Species

While the utilitarian

perspective and calculation of value usually revolve around what is

good for human beings, there is arguably a broader perspective

relating to utilitarianism that could be taken. According to

Harry Wilson

in "Finding and Ethical Basis for Section 7 of the

Endangered Species Act,"

"To use a

utilitarian system one must be reasonably sure of the

consequences of any action. That means that nearly comprehensive

scientific and economic data must be available. As one may well

imagine, that is rarely the case. Consequently, utilitarianism

is often used today in a reckless fashion. Decisions are made

today with only a very short examination of the potential

results. This bodes ill for environmental and bio-diversity

concerns, since quantifiable anthropocentric impacts are

difficult to assess and usually pose little short-term damage to

human life." "..it is often hard to demonstrate the utility of

seemingly insignificant species" .. "... especially when faced

with the immediate concerns of humans living nearby.

Utilitarianism is especially bad at justifying absolute

prohibitions .. since to a utilitarian a case-by-case evaluation

of the potential impacts of placing a species on the list would

seem better suited to promoting the overall "good."

Wilson goes on to

describe a broader approach to utilitarianism in which the intrinsic

value of animals and species might be possible. Wilson goes back to

the early utilitarianism of Bentham and Mill and suggests that their

philosophy defined the "greatest happiness" as necessarily

encompassing more than mere human happiness. This recognition was

based upon their belief that animals, as well as humans, could

experience evil and pain, and by logic, could also experience

pleasure and happiness. When this understanding, however, is applied

to "endangered species" then there is not difference in the "value"

of endangered versus non-endangered species. In fact, utilitarianism

does not assign any value to a "species" - period. Consequently,

Wilson concludes, utilitarianism holds little promise for protecting

endangered species.

Pressures and Responsibilities of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service

USFWS

& USGS Perceptions of Challenges

According to the

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and

it's sister agency the U.S.

Geological Survey significant

challenges facing the agencies include:

Significant future

impacts to biodiversity and ecosystem function emanating from:

-

Biotechnology:

In terms of biotechnology, this constitutes a potential

conservation tool, but in the case of genetic engineering, this

tool can

"pose potential threats to

ecological functioning that need to be assessed."

-

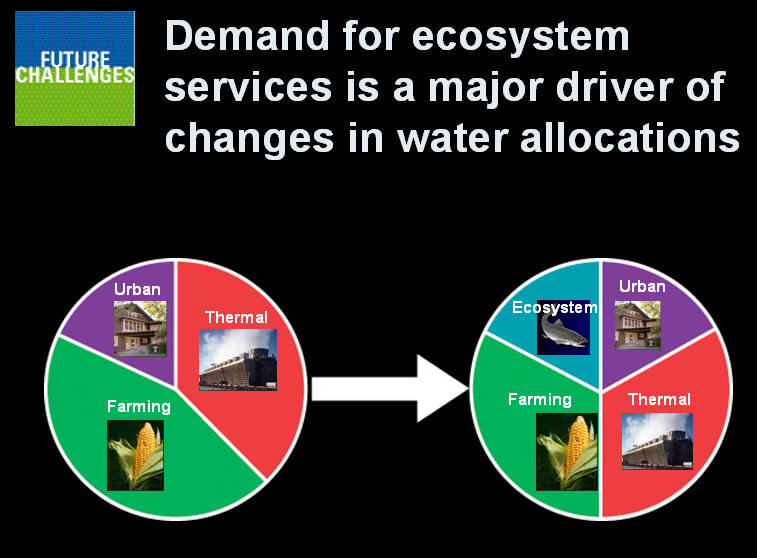

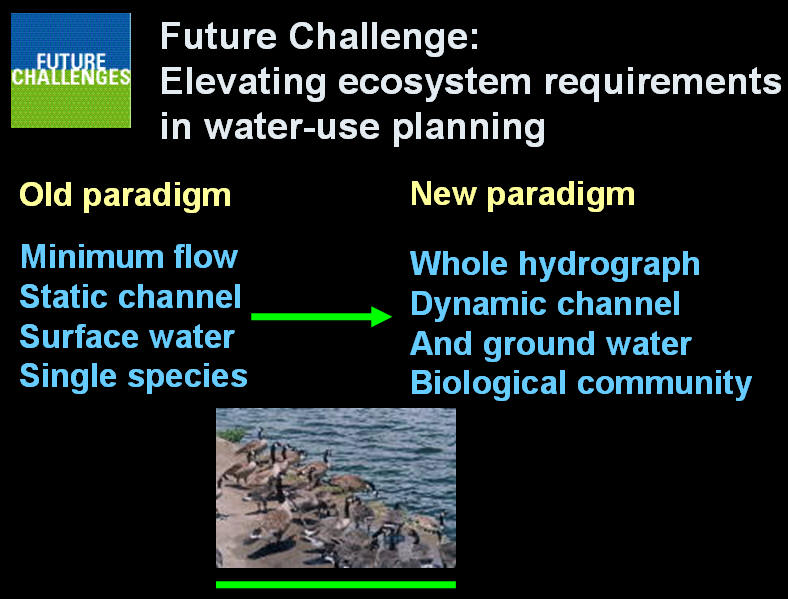

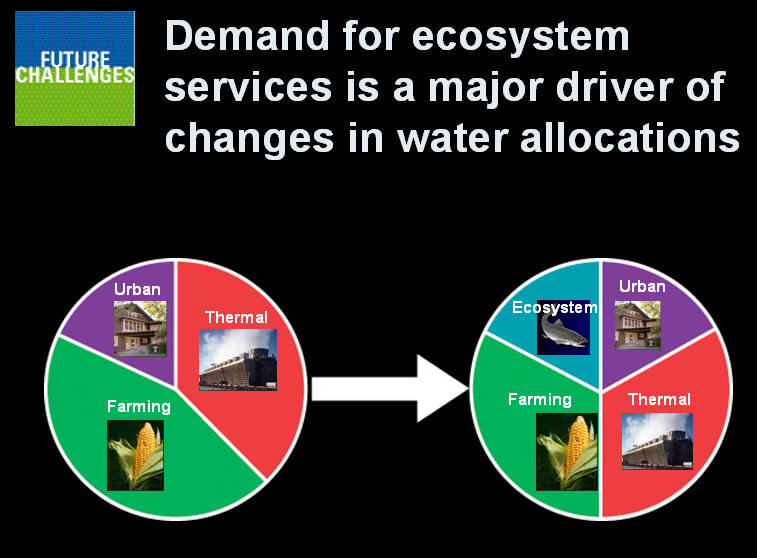

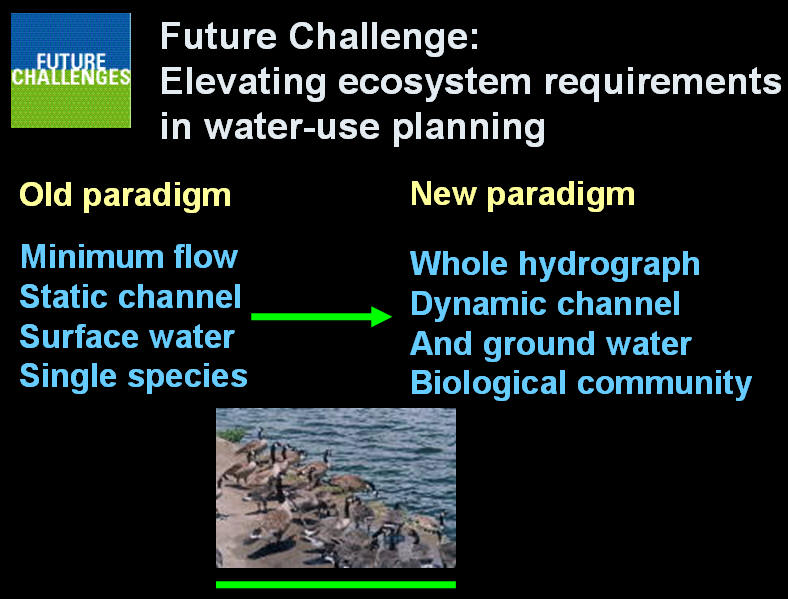

Water for

Ecological Needs: Water resources are expected to be under

significant stress due to population increases, industrial

growth worldwide, as well as from overall changes in the use and

allocation of water resources. As illustrated below,

ecosystem water use will increasingly be "carved" out of urban,

agricultural and thermal uses. Moreover, the USFWS and the USGS

find themselves considering a transition from an old ecosystem

water use planning paradigm to a new one (see second

illustration below).

Consequently, these two

agencies committed themselves to a set of actions to deal with each

of the challenges identified above. These include:

"Results: Invasive Species:

-

Be strategic: focus on species and

habitats where USGS & FWS can make a difference.

Increase use of FWS lands.

-

Emphasize research and management for

detection, prevention and control efforts early

in the invasion process.

-

Focus on understanding

linkages between global change, biotechnology, and

invasive species

Results: Biotechnology:

-

Planning for the use of biotechnology in

conservation should proceed due to great potential

benefits, but with deliberation and great care.

-

Information exchange and broader

partnerships with academia and industry are essential

for success.

-

Risk assessment

procedures and the need for policy changes must be

addressed very soon

Results: Climate Change:

-

Develop and implement specific monitoring

strategies tailored to effects on wildlife and

habitats.

-

Focus planning and management efforts at

the ecosystem level.

-

Rethink the design of reserves and

protected areas.

-

Climate Change

complicates planning for the other three challenges.

Results: Water for Ecological Needs

-

Place greater emphasis on whole systems

approaches.

-

Improved systems understanding will allow

resource managers to prioritize areas and develop

strategies for vulnerable systems.

-

Need for predictive models of potential

systems effects under different land/water management

regimes."

The USFWS is also

challenged in its efforts to

protect forest habitat for endangered and threatened species.

They do so by working in conjunction with the U.S. Forest Service in

planning for the "thinning" of forests to prevent forest fires.

Indeed fire prevention is a major challenge for the work of the

agency.

Other challenges include identifying and designating critical

habitats, habitat protection through "cooperative conservation," and

determining "critical habitat exclusions."

Report from The Union of Concerned Scientists

Unfortunately, USFWS and

USGS also face political and funding pressures - especially in light

of the costs of the Iraq War, homeland security, immigration reform

and emergency aid for natural disasters such as in the case of

hurricane Katrina. The

Union of Concerned Scientists has

been particularly vocal in their concern. They accuse the Bush

administration of letting "politics

trump science." Accordingly, they claim:

"Political

intervention to alter scientific results has become pervasive

within the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), according to a

survey of its scientists released today by the Union of

Concerned Scientists (UCS) and Public Employees for

Environmental Responsibility (PEER). As a result, endangered and

threatened wildlife are not being protected as intended by the

Endangered Species Act, scientists say.

The two organizations distributed a 42-question survey to more

than 1,400 USFWS biologists, ecologists, botanists and other

science professionals working in Ecological Services field

offices across the country to obtain their perceptions of

scientific integrity within the USFWS, as well as political

interference, resources and morale.

-

Nearly half of all respondents whose work is

related to endangered species scientific findings (44

percent) reported that they "have been directed, for

non-scientific reasons, to refrain from making jeopardy or

other findings that are protective of species." One in five

agency scientists revealed they have been instructed to

compromise their scientific integrity-reporting that they

have been "directed to inappropriately exclude or alter

technical information from a USFWS scientific document;"

In essays submitted on the topic of how to

improve the integrity of scientific work at USFWS, one biologist

wrote, "We are not allowed to be honest and forthright, we are

expected to rubber stamp everything. I have 20 years of federal

service in this and this is the worst it has ever been." By far,

the most frequent concern raised by the scientists in the

written responses was political interference.

"The survey results illustrate an alarming disregard for

scientific facts among political appointees entrusted to protect

threatened and endangered species," said UCS Washington

Representative Lexi Shultz. "Employing scientists only to

undermine their findings is at best a mismanagement of public

resources and at worst a serious betrayal of the public trust."

A number of the essays spoke to the climate of fear within the

agency. One biologist in Alaska wrote, "Recently, [Department of

Interior] officials have forced changes in Service documents,

and worse, they have forced upper-level managers to say things

that are incorrect…It's one thing for the Department to dismiss

our recommendations, it's quite another to be forced (under

veiled threat of removal) to say something that is counter our

best professional judgment." A manager wrote, "There is a

culture of fear of retaliation in mid-level management. If the

manager were to speak out for resources, they fear loss of jobs

or funding for their programs." And a biologist from the Pacific

region added that the only "hope [is] we get sued by an

environmental or conservation organization."

"Political science, not biology, has become the dominant

discipline in today's Fish & Wildlife Service," concluded PEER

Program Director Rebecca Roose, who worked with current and

former USFWS employees on survey design. "Like the trainer who

hobbles a horse and then laments that it does not run fast, the

politicians who complain about the lack of 'sound science' in

the administration of the Endangered Species Act are often the

very ones who intervene behind closed doors to manipulate

scientific findings when they impede development projects."

Despite agency directives not to reply-even on their own

time-nearly 30 percent of all the scientists returned surveys."

Bush Administration 2004 Budget Request for Department of

Interior Programs

While the accuracy

of the allegations of the Union of Concerned Scientists is difficult

to assess, the priorities of the Bush Administration in regard to

the USFWS are a matter of public record, such as in the case of this

2004 administration budget request

to the U.S. Congress.

"Land and Water

Conservation Fund

The cornerstone of

our request is the Administration’s commitment to full funding

of the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Our request includes

$415.6 million for Service programs funded through the Land and

Water Conservation Fund, a $79.6 million increase over 2004.

This includes most of the Service portfolio of grant programs as

well as the Secretary’s emphasis on conservation partnerships

through a Cooperative Conservation Initiative in the Resource

Management account.

In recognizing the

importance of opportunities for conservation of threatened and

endangered species through partnerships with private landowners,

we are requesting $60.0 million for the Landowner Incentive and

Private Stewardship programs, an increase of $23.0 million above

the 2004 enacted level. In 2004 these programs will support

innovative partnerships in 42 states and assist many individuals

and groups engaged in local, private and voluntary conservation

efforts that benefit federally listed, proposed, candidate or

other at-risk species. The 2005 request will significantly build

upon this success.

We request $90.0

million for the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation

Fund, $8.4 million above the 2004 enacted level. Additional

resources for this program will increase our ability to provide

funds to states and territories to implement recovery actions

for listed species, implement conservation measures for

candidate species, and perform research and monitoring critical

to conservation of imperiled species. The proposed funding level

would provide $50.0 million to support Habitat Conservation Plan

Land Acquisition grants; $17.8 million for Recovery Land

Acquisition grants to help implement approved species recovery

plans; $10.9 million for traditional grants to states; and $8.8

million for HCP planning assistance to states.

Funding totals $80.0

million, including a $6.0 million tribal set-aside, for State

and Tribal Wildlife Grants, an increase of $10.9 million over

the FY 2004 enacted level. The bulk of this increase will

support the completion of the required State Comprehensive

Wildlife Plans.

The budget proposes

$54.0 million for the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund,

an increase of $16.5 million or 44 percent over the 2004 enacted

level. These matching grants support wetlands and migratory bird

conservation with private landowners, states, NGO’s, and other

partners.

We request $45.0

million for high-priority acquisition of land and conservation

easements from willing sellers. This is increase of $6.9 million

above the 2004 enacted level. Priorities include $10.0 million

for the Quinnault settlement, $2.6 million for the Baca Ranch,

and $4.6 million in the Klamath Basin to enhance water quality

and restore habitat.

The Cooperative

Conservation Initiative includes our highly successful Partners

for Fish and Wildlife Program, our Coastal Program, National

Wildlife Refuge system challenge cost-share grants, and the

Joint Ventures program. The budget provides $13.9 million in

increased funding for these programs. We will discuss the

components of the CCI in the testimony that follows.

Operations –

Resource Management Account

Our main operations

account is funded at $951.0 million in the request, a net

decrease of $5.5 million below the 2004 enacted level. This

reduction largely reflects decreases from one-time Congressional

projects that were included in the 2004 enacted funding level.

The budget includes $15.9 million in program increases which are

discussed in my testimony and $8.1 million in fixed cost

increases. The budget also includes savings from lower-priority

program line items, and an overall reduction of $1.8 million

tied to expected savings from improved vehicle fleet management.

These savings have been redirected towards high priority

initiatives in the request.

Science Excellence Initiative

An increase of $2.0

million will be used for the Science Excellence Initiative, to

provide managers better access to the best available science and

better ability to apply that science toward adaptive management.

This initiative is the beginning of a renewed commitment to

scientific excellence that will support the mission and

employees of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the

Secretary’s 4 C’s vision. This will be accomplished by expanding

partnerships with organizations like the U.S. Geological Survey,

universities, and professional societies; by applying scientific

information to begin developing explicit population and habitat

goals to better guide conservation efforts; and applying

state-of-the-art tools and techniques, including models linking

populations and habitats, spatial analysis, and more strategic

survey and monitoring that supports adaptive management and

research.

Endangered

Species

The budget request

includes a total of $279.4 million for endangered species

programs, a $23.8 million increase. This includes $129.4 million

for the operations program and $150 million for partnership

grant programs. The budget includes an increase of $31.4 million

for the grant programs that can help to achieve Endangered

Species Act recovery goals in a partnership with states, Tribes,

local jurisdictions and private citizens. In 2005, with the

increase to the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund

for example, the Fish and Wildlife Service will increase by 20

percent the number of partnerships and cooperative efforts to

stabilize, improve and recover endangered species. The $129.4

million request for the endangered species operations program is

a net reduction of $7.6 million below the 2004 enacted level.

The program funding will support operations that enhance

implementation of the Endangered Species Act. Within this total,

the Service requests $17.2 million, a $5.1 million increase

above the 2004 enacted level for Listing. Increased funding is

required to meet resource protection goals and address the

growing litigation-driven workload in the listing program.

Partners for Fish

and Wildlife

To date, the

Partners program has worked with 33,100 private landowners

through voluntary partnerships to implement on-the-ground

habitat restoration projects. We request $50.0 million, a net

increase of $7.6 million, to accelerate this highly effective

program for voluntary habitat restoration on private lands as

part of the Secretary’s Cooperative Conservation Initiative. A

requested general program increase of $5.0 million will allow

the Partners Program to improve the health of watersheds and

landscapes that are DOI managed and increase our capability to

enter into meaningful partnerships resulting in on-the-ground

habitat restoration. An increment of $1.0 million will be used

to extend partnerships in combating tamarisk and associated

noxious weeds, on federal and other lands in the Southwest.

In addition, we

request increases of $5.0 million for the High Plains

Partnership to conserve declining species and their habitats on

private lands throughout 11 states; and $6.2 million for the

Upper Klamath Basin Restoration Initiative to help forge a

long-term solution to conflicts over water and land management

to restore habitat, remove fish migration barriers, and improve

the health of the Klamath basin to benefit farmers, tribes, and

wildlife.

Coastal Program

As part of the

Secretary’s Cooperative Conservation Initiative, we request

$13.1 million for our Coastal Program, including a general

program increase of $3.5 million to help protect and restore

high priority coastal habitats. In addition to on-the-ground

restoration, maps, habitat surveys, and grant application

assistance will continue to help communities plan and implement

projects that balance economic development and the coastal

resources that make these communities desirable places to live

and work.

Migratory Bird

Management

Our 2005 request

places a major emphasis on a core Service responsibility:

conservation and management of Migratory Birds. To benefit

migratory bird species, we request a net increase of $4.6

million for our Migratory Bird Conservation and Monitoring

Program including an increase of $1.2 million for our Migratory

Bird Joint Ventures Program.

Requested increases

include $1.0 for Environmental Impact Studies, $250,000 for

Webless Migratory Bird Conservation efforts, $655,000 for the

Harvest Information Program, and $2.1 million for migratory bird

surveys, monitoring and assessment activities.

Of note, a $700,000

increase will fund improvements to migratory bird permit

processing along with a similar increase of $500,000 to

modernize the International Affairs Service Permits Issuance and

Tracking System, or SPITS.

The Service also

requests a $1.2 million increase for the Migratory Bird Joint

Venture program that will provide a total of $11.4 million for

the program as part of the Secretary’s Cooperative Conservation

Initiative. This increase is also tied to a $16.5 million

increase in the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund. This

successful program protects and restores critical habitats for

diverse migratory bird species across all of North America, both

on, and to a greater extent off, Service lands. The requested

increase combined with the other dedicated funds is expected to

be matched by at least $341 million of partner’s funds.

National Wildlife

Refuge System

We request $387.7

million for National Wildlife Refuge System operations and

maintenance. Although this is a net decrease of $3.8 million

below the 2004 enacted level. It reflects the reduction of $5.0

million for a one time transfer from the National Park Service

for monitoring in Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge.

An increase of $2.2

million – for a total of $12.0 million -- for the Challenge Cost

Share program will meet expanded opportunities for natural

resource restoration partnerships. This is a component of the

Cooperative Conservation Initiative. With additional funding,

refuges and partners will build on the current program and

pursue results-oriented conservation projects consistent with

the Cooperative Conservation Initiative criteria to promote

citizen stewardship through cost-shared projects that restore or

conserve natural resources. The National Wildlife Refuge System

has developed additional initiatives that provide expanded

opportunities for natural resource restoration partnerships.

Recent projects leveraged more than $1.5 for every $1 in federal

funding.

The National

Wildlife Refuge System law enforcement program will continue

compliance with the Secretary’s directive to implement law

enforcement reforms and address issues identified by the

International Association of Chiefs of Police and the Inspector

General with an increase of $3.6 million. An additional 20 law

enforcement officers will be hired, including $900,000 to hire

seven additional law enforcement officers to be placed along our

Southern border at San Diego NWR (CA), Buenos Aires NWR (AZ),

and Cabeza Prieta NWR (AZ).

Last, the refuge

program will use $1.0 million to develop strike teams to quickly

respond to infestations of brown tree snake, tamarisk, leafy

spurge, and yellow star thistle in Hawaii and the Pacific

Islands and the Dakotas.

Fisheries

For the National

Fish Hatchery System, we request $57.0 million. This includes an

operations programmatic increase of $840,000 and a maintenance

increase of $1.0 million. We will focus the additional

operations funds in priority areas identified in the DOI

Strategic Plan, the Fisheries Program’s “Vision for the Future,”

the Administration’s PART Review, and more specific Regional

step-down plans linked to DOI goals. The bulk of this increase

will support resource protection goals by sustaining biological

communities on DOI managed and influenced lands and waters.

We request $46.8

million, a net decrease of $9.5 million under the 2004 enacted

level, for the Fish and Wildlife management assistance program.

Of note, sea lamprey overhead costs are funded at $889,000, the

2004 enacted level, and the highest priority aspects of the

Yukon River Salmon Treaty will be implemented with $3.0 million,

slightly lower than the 2004 enacted level.

International

Conservation

Along with the

permits request discussed above, we request $9.5 million for the

Multinational Species Conservation Fund. Within this fund, we

propose to include $4.0 million funding for the Neotropical

Migratory Bird Conservation Fund. The service request provides

$1.5 million for the Rhinoceros and Tiger Conservation Fund, and

$1.4 million each for the African Elephant Conservation Fund,

the Asian Elephant Conservation Fund, and the Great Ape

Conservation Fund.

General Operations

For general

operations, we request $134.5 million, a net increase of $4.6

million above the 2004 enacted level for Central Office

Operations, Regional Office Operations, Servicewide

Administrative Support, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation,

National Conservation Training Center, International Affairs,

and the Science Excellence Initiative. Increases include funding

for audit costs and the Enterprise Services Network and E-Gov

projects."

Critique of Adequacy of Department of Interior Funding

However, there remains

concerns regarding the extent to which the U.S. Department of the

Interior (to which the USFWS reports) has sought adequate funding

from Congress to carry forward the litigation required to enforce

the ESA. For instance, here is

a critique of the adequacy of funding that was made in 2000:

"The U.S. Fish &

Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service have

lost over 100 lawsuits in the last decade challenging their

failure to place imperiled species on the Endangered Species

list. The Center for Biological Diversity, for example, has

completed 54 listing cases since 1993 and has lost only one.

With no legal justification for its delays, the Fish & Wildlife

Service has increasingly turned away from legal to budgetary

arguments. In virtually all court cases, and in the media, it

pleads that Congress has not appropriated enough funds to carry

out the legally mandated duties of the Endangered Species Act

IS CONGRESS

REALLY TO BLAME? To the extent that Congress

appropriates the budget and has been hostile toward endangered

species protection, the argument appears convincing....to the

media and public at least. The courts have repeatedly rejected

budgetary argument. In a recent California case (Center

for Biological Diversity v. Babbitt, CIV 99-03202 SC, 9/00),

Judge Samuel Conti opined: "the solution of being over-obligated

and under-funded rests with Congress, and not with the court."

So the courts have ordered the USFWS to find the money elsewhere

if the listing program line item is lacking.

Congressional

appropriations begin with a formal budget request from the

Department of Interior to Congress. The U.S.D.I. Inspector

General concluded in 1990 that the Department of Interior needed

$144 million to address the listing backlog. Yet the Department

has never once asked Congress for anything near that level. The

Clinton administration, for example, never asked for more than

$8.2 million (see figure 1). Indeed it never asked for as much

funding as the Bush administration did in 1992 ($10 million).

Even worse, requests for funding of the listing program

experienced a decline during the Clinton years. This was not a

function of an overall decline in the Endangered Species Act

budget. Overall budget requests grew on Clinton's watch from

$77.9 to $123.3 million. Every Endangered Species Act budget

item increased substantially except the listing program

which decreased (see figure 1).

A SPENDING

CAPS TO SUBVERT THE COURTS. That the Department of

Interior would purposefully reduce its listing budget (by

reducing its request to Congress) even as it faces a growing

backlog of imperiled species, listing petitions, and court

orders, is not the strangest of its budgetary actions. In every

budget request from FY1998 through FY2001, the Secretary of the

Interior has asked Congress to introduce a rider to the Interior

Appropriations Bill, banning the use of any money from outside

the listing budget to implement court orders or otherwise list

species or designate critical habitat. It has done this because

the courts have consistently refused to accept budgetary

restraints as a valid reason for not protecting endangered

species. With the legislative cap, the administration had hoped

to tie the hands of the judiciary, such that obeying the

Endangered Species Act would require violating the

appropriations act.

Far from being

hampered by Congress, the Department of Interior invented and

lobbied Congress to include the spending cap rider. The House

Report on the FY1998 Interior Appropriations Bill explains: "As

requested by the Department of Interior, the [House] managers

reluctantly have agreed to limit statutorily the funds for the

endangered species listing program." This strategy, like other

administrative assaults on the Endangered Species Act listing

program, has been a hindrance, but has not stopped the federal

courts or brought the listing rate down to the pre-1992 era. Its

primary impact has been to cause enormous stress among its

chronically understaffed, underfunded field offices.

FIGHTING

COURT ORDERS FOR A BALANCED BUDGET. The Department of

Interior's desire not to have a fully funded, or even close to

adequately funded, listing program was revealed in a recent case

involving four Hawaiian invertebrates (Center for Biological

Diversity v. Babbitt). Judge

Mollway rejected the agency's reliance on an inadequate

Congressional appropriation:

"USFWS has not

presented competent evidence demonstrating that it even applied

for the funds to designate the Four Invertebrates' critical

habitat or that it would have been unsuccessful had it done

so...The court finds that...USFWS must at least request the

funds necessary to designate the Four Invertebrates' critical

habitats before USFWS can say that it is unreasonable for it to

designated those critical habitats earlier than the fall of

2004."

Mollway, therefore,

ordered the agency to do the obvious: request adequate funds

from Congress to do its job in FY2001. If, despite decreasing it

listing budget request between FY2000 and FY2001, the Department

of Interior had any interest in obtaining more funds, this court

order would have been the perfect vehicle to go back to Congress

with. The federal court was essentially acting as an ally to

help the Department justify increased funding. Instead, the

Department opposed Mollway's order on technical legal grounds

and eventually convinced her to rescind that portion of her

order. Instead, she simply ordered the USFWS to designate

critical habitat and let it worry about how to do it.

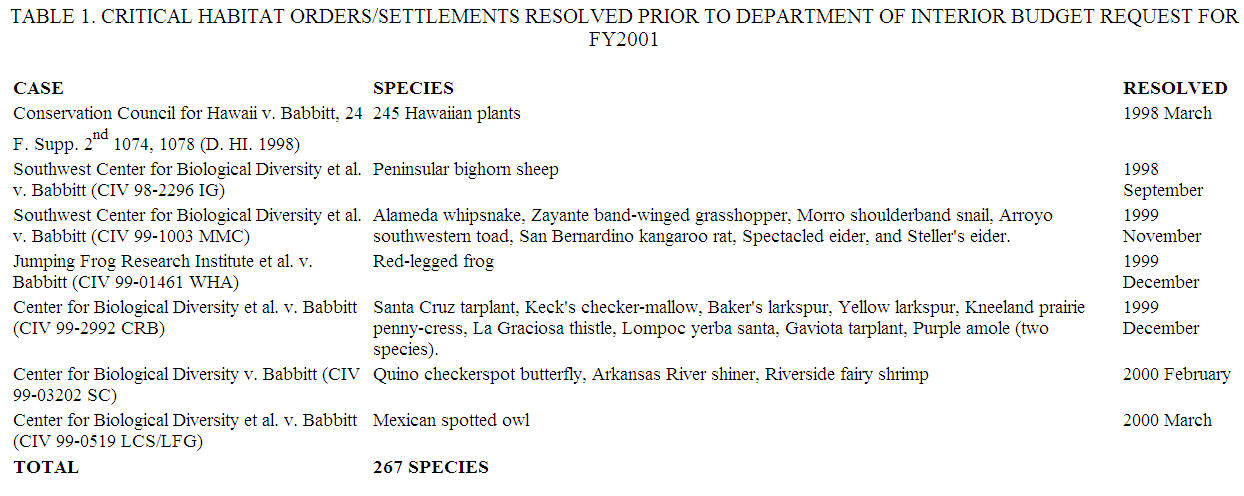

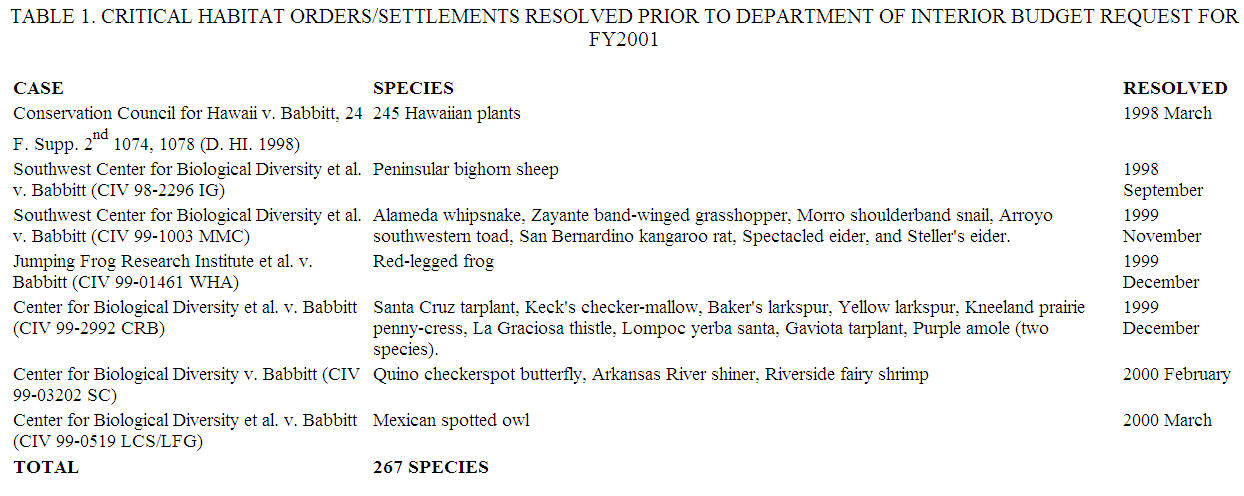

A PERFECT

BUDGET TO JUSTIFY A MORATORIUM.

The USFWS has

presented its 2001 listing moratorium as if it first had a

budget, then got slapped with expensive court orders, and now

has to grudgingly issue a moratorium because it has unexpectedly

run out of money. The blame in this story is spread out between

Congress, the courts and the environmentalists who brought the

lawsuits. But the Department of Interior knew exactly how much

money it would need to address the court orders and listing

backlog before it went to Congress. The Department of

Interior makes its budget request for the following year in

March. Of the 300 species for which the USFWS is under court

order to designate critical habitat, at least 265 were ordered

or settled before March, 2000 (see table 1). The Department of

Interior had these rulings in hand and knew what the vast

majority of its work load would be before it presented

its budget request to Congress. Nonetheless, it not only failed

to ask for enough money. Indeed, it asked for $335,000 less

than it asked for in FY2000.

The moratorium,

therefore, is not a product of unexpected and unmanageable court

orders. It is the product of a cynical decision by the

Department of Interior to not request enough money to do the job

at hand. Interior knew exactly what the consequences would be

March 2000 when it submitted the grossly inadequate budget

request. The issuance of the listing moratorium in November was

caused by the March budget request, not court orders issued

after March. In fact, very few critical habitat court orders

were issued after March, 2000.

GAO

Report on the Department of Interior

In 2003,

GAO issued a

report regarding the performance of the Department of Interior and

made the following observations:

"Overall, the

Department of the Interior has made some or good progress in

addressing three of the six key management challenges GAO

identified in 2003. Despite this progress, the department

continues to face challenges related to its ecosystem

restoration efforts, deferred maintenance backlog, and financial

management. Generally, for the other three key management

challenges—Indian and island programs, management of the

national parks, and land exchanges and appraisals, GAO has not

conducted sufficient new audit work since its 2003 report to

fully assess the department's progress in addressing those

challenges."

Limits on Federal Agency Actions

The following cases are

illustrative of limitations that may be imposed upon federal

regulatory actions in regard to the Endangered Species Act.

TVA v.

Hill

Tennessee Valley Authority v.

Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978) (The Snail Darter case)

The Facts

The Tennessee Valley Authority

(TVA), established by President Franklin Roosevelt during the

Great Depression to bring electricity to parts of the rural

south, began construction of the Tellico Dam and River Project

on the Little Tennessee River in 1967. The goal of the project

was to create not only hydroelectric power, but shoreline

development, recreational opportunities, and flood control. When

fully operational, the planners intended the Tellico Dam to

impound water covering approximately 16,500 acres, converting

the Little Tennessee's shallow, fast-flowing waters into a deep

reservoir some 30 miles in length.

In 1973, an ichthyologist

[ichthyology is the study of fish] exploring the area that would

be flooded by the Tellico Dam, discovered a previously unknown

species of fish: a three-inch, tannish-colored perch called the

Snail Darter. Studies of this small fish showed that the whole

species lived in that small part of the Little Tennessee River

which would be turned into the Tellico Dam Reservoir. To protect

the Snail Darter and its habitat, the Secretary of the Interior

listed it as an Endangered Species.

The Lawsuit

District Court (trial court):

In 1976, a citizens group, including farmers, sportsmen,

archaeologists, and representatives of the Cherokee Nation sued

the TVA in Federal District Court to "enjoin" [stop]

construction of the dam and creation of the reservoir arguing

that these actions would violate the Endangered Species Act by

causing the extinction of the Snail Darter. The plaintiffs

argued that once a federal project is shown to jeopardize an

endangered species, a court must issue an "injunction" that will

halt the activity.

The District Court agreed with

the plaintiffs that completion of the Tellico Dam project would

indeed destroy the Snail Darter's critical habitat and probably

lead to its becoming extinct. In spite of this, the Court said:

-

the project was 80% complete

(and stopping the project would waste the millions in

taxpayer money already spent), and

-

the Congress continuously

allocated funds for the project even though it knew about

the Snail Darter's plight.

Therefore, the project could be

completed.

In its decision, the Court posed

an interesting question: If it ruled for the Snail Darter,

wouldn't it be possible that projects 99% completed could be

derailed if an endangered species was discovered before the

final 1% was accomplished?

Following the District Court's

decision, the TVA informed Congress that it was continuing its

efforts to save the Snail Darter (by transplanting it to another

section of the Little Tennessee River) and Congress provided

funding to complete the project.

The Court of Appeals:

The federal Appeals Court, reviewing the ruling of the District

Court, disagreed with the District Court's decision and demanded

that all activity at the Tellico Project which "may destroy or

modify the critical habitat of the Snail Darter" be stopped. The

Court said that the project could not continue until one of two

things occurred:

-

Congress legislatively

exempted the Tellico Project from compliance with the

Endangered Species Act, or

-

the Snail Darter was no

longer in danger of extinction.

As to the question asked by the

District Court whether a project could be stopped dead in its

tracks on the eve of completion, the Appeals Court said that

"the detrimental impact of a project upon an endangered species

may not always be perceived before construction is well

underway." The Appeals Court said that "whether a dam is 50% or

90% completed is irrelevant in calculating the social and

scientific costs attributable to the disappearance of a unique

form of life."

Following the Court of Appeals

decision, Congress again decided to fund the Tellico Dam

Project, but now included additional moneys for TVA's efforts to

relocate the Snail Darter to a suitable habitat beyond the reach

of the Tellico Dam reservoir.

The Supreme Court:

The Supreme Court, reviewing the ruling of the Appeals Court,

asked itself two questions:

-

Would the TVA violate the

Endangered Species Act if it completed and operated the

Tellico Dam as planned?

-

If

the TVA's

actions would violate the Act, is an "injunction" the

appropriate way to address the problem?

The Supreme Court answered yes to

both questions. Chief Justice Warren Burger explained the

Court's thinking about the Snail Darter and the Endangered

Species Act:

"It may seem curious to some

that the survival of a relatively small number of three-inch

fish among all the countless millions of species [that

exist] would require the permanent halting of a virtually

completed dam for which Congress has expended more than $100

million. The paradox is not minimized by the fact that

Congress continued to appropriate large sums of public money

for the project, even after ... [it knew about the dam's ]

... impact upon the survival of the snail darter".

"One would be hard pressed to

find a statutory provision whose terms were any plainer than

those in Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act. Its very words

affirmatively command all federal agencies "to insure that

actions authorized, funded, or carried out by them do not

jeopardize the continued existence" of an endangered species or

"result in the destruction or modification of habitat of such

species". This language admits of no exceptions."

"This view of the Act will

produce results requiring the sacrifice of the anticipated

benefits of the project and of many millions of dollars in

public funds. But examination of the language, history, and

structure of the legislation ... indicates beyond doubt that

Congress intended endangered species to be afforded the highest

of priorities.

The Supreme Court agreed with the

Appeals Court. The Tellico Dam project could not be completed.

The rulings of the Supreme Court

and the "God Committee" should have ensured the survival of the

Snail Darter. In mid-1979, however, Senator Howard Baker (the

Republican Senate minority leader) and Congressman John Duncan,

both from Tennessee, buried a small provision into a large piece

of legislation pending before the Congress. This provision undid

the Supreme Court's decision in TVA v. Hill and provided that

the Tellico Dam project could be completed without further legal

delay. The project was completed in late-1979.

No Snail Darters survived in that

part of the Little Tennessee River impacted by the Tellico Dam

project. Small populations of the Snail Darter, however, were

subsequently discovered. As a result, the Department of Interior

now lists the species as "threatened" rather than "endangered".

The Fate of the Snail Darter

"Following the Supreme Court's

decision, the "God Committee" [a.k.a. “God Squad”], created

under Section 7 of the Act, assembled to consider exempting the

Snail Darter and the Tellico Dam project from the restrictions

of the Endangered Species Act. On the basis of economic rather

than ecological grounds, the Committee denied the Tellico

project an exemption."

By wan of

information, here is a bit more information about the so-called

"God Squad."

The God Squad

"A 1978

amendment to section 7 of the act allows agencies to

implement an action that would be likely to jeopardize a

listed species provided the action is declared exempt by a

cabinet-level committee called the Endangered Species

Committee or, informally, the "God squad" (Sec.

7(e). The committee must

base its decision on a set of criteria outlined in

Sec. 7(h),

including that:

-

The benefits of the action must

outweigh the benefit of proposed alternative actions;

-

The action must be in the public

interest and of national or regional significance; and

-

Reasonable mitigation measures must

be established to minimize the impact on the listed

species.

The Endangered

Species Committee is convened only when an application is

made for such an exemption and that application meets

certain specific requirements. Historically, the committee

has been convened only a few times and has granted

exemptions even less frequently."

The "God Squad",

consists of seven members (Secretaries of the Agriculture,

Army, and Interior, Chairman of the Council of Economic

Advisors, Administrator of the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration, and one individual from the

affected state). According to statute, five of these members

must concur that an action will likely jeopardize the

viability of a listed species, or must conclude that the

issue before them is of regional or national importance, or

determine that the benefits to be derived from a proposed

action demonstrably outweigh the alternative benefits of

preserving the species. Regardless of their decision, they

must assure themselves, to the maximum extent possible, that

there are no reasonable and prudent alternatives to their

decision for final action.

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife

The famous "Lujan"

case is actually a set of two cases beginning with

Lujan v. National Wildlife Federation

[497 US 871 (1990)] (a.k.a. Lujan I) (argued before the Supreme

Court by the current Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John

Roberts) followed by

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife

[504 U.S. 555 (1992)] (Lujan II). John Echeverria and Jon T.

Zeidler of Georgetown University's Environmental Law and Policy

Institute comment upon these two important cases in their paper

"Barely

Standing: The Erosion of Citizen "Standing" to Sue and Enforce

Environmental Law." They describe what transpired with these

cases in the following words:

"Lujan v. National Wildlife Federation (Lujan

I)

The Court, by a vote of 5 to 4, ruled that the National

Wildlife Federation lacked standing to challenge a decision

of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to review the

classification of federal lands and open them to various

kinds of resource development. The Federation contended that

the BLM had acted in violation of the Federal Land Policy

and Management Act and had failed to prepare an

environmental analysis as required by the National

Environmental Policy Act. To establish its standing, the

Federation filed affidavits of several of its members who

asserted that they used land "in the vicinity" of federal

lands affected by the agency's decision, and that opening

these lands to development would interfere with

"recreational use and aesthetic enjoyment" of the lands.

The Court, reversing a federal appeals court,

ruled that the government was entitled to summary judgment

based on the standing issue. The Court concluded that the

affidavits pointed to types of injuries that would

ordinarily be sufficient to establish standing. But the

Court ruled that the members' assertions that they used

lands "in the vicinity" of the specific lands allegedly

threatened by the agency decision were inadequate to

demonstrate that they were "actually affected" by the BLM's

decision.

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife (Lujan II).

Two years later, the Court expanded upon

Lujan I by ruling that Defenders of Wildlife lacked standing

to challenge a determination by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service that the

consultation requirement of section 7 of the Endangered

Species Act (ESA) did not apply to federal government

actions in foreign nations.

Justice Scalia, speaking for the Court,

concluded that Defenders had failed to establish the type of

"imminent" injury necessary to satisfy the "injury in fact"

requirement for Article III standing. Defenders relied on

several affidavits of members who were interested in

endangered species conservation and had visited the sites of

two foreign development projects which threatened particular

species, but who could not specify when they planned to

return to these sites. Justice Scalia said that this type of

"some day" intention was inadequate to confer standing.

Moreover, Justice Scalia said that a demonstrated

professional interest in a particular species was

insufficient, by itself, to establish standing to challenge

a foreign development project which threatened the species.

Speaking for himself and three other

Justices, Justice Scalia also concluded that Defenders

failed to satisfy the "redressability" requirement for

standing. He stated it was unclear whether other federal

agencies would believe they were bound by a revised

regulation, or whether these foreign development projects

(which were also receiving support from other nations) would

actually be halted if the U.S. withdrew its support.

Justice Scalia laid out the theory of

standing he outlined prior to his appointment to the Court

and made it a formal part of U.S. Supreme Court standing

doctrine. He said that standing "depends considerably upon

whether the plaintiff is himself an object of the action (or

foregone action) at issue. If he is, there is ordinarily

little question that the action or inaction has caused him

injury, and that a judgment preventing or requiring the

action will redress it. When, however, as in this case, a

plaintiff's asserted injury arises from the government's

allegedly unlawful regulation (or lack of regulation) of

someone else, much more is needed."

The most significant aspect of Lujan II is

Justice Scalia's rejection of the idea that Congress can

confer standing by adopting an expansive citizen suit

provision. Defenders sought to establish its standing based

on the provision of the Endangered Species Act which

authorizes "any person" to bring a civil suit "to enjoin any

person . . . who is alleged to be in violation of any

provision of this chapter." To permit Congress to confer

standing through such a provision, Justice Scalia said,

would authorize individuals to sue to enforce the

"undifferentiated public interest" in seeing that the laws

are enforced. This would violate the principle of separation

of powers, according to Justice Scalia, by "enabl[ing] the

courts, with the permission of Congress, to assume a

position of authority over the governmental acts of another

and co-equal department."

Justice Kennedy (and Justice Souter) joined

in most of Justice Scalia's majority opinion, but filed a

separate concurrence. Significantly, they qualified Justice

Scalia's discussion of the issue of Congress' authority to

confer standing by enacting citizen suit provisions. Justice

Kennedy wrote that "Congress has the power to define

injuries and articulate chains of causation that will give

rise to a case or controversy where none existed before, and

I do not read the Court's opinion to suggest a contrary

view." He emphasized that "as government programs and

policies become more complex and far reaching, we must be

sensitive to the articulation of new rights of action that

do not have clear analogs in our common-law tradition."

Thus, to an important, if uncertain degree, Justice Kennedy

(and Justice Souter) left open the possibility that Congress

can still enact legislation conferring standing to sue."

|