|

Introduction

The first part of

this overview of the Endangered Species Act

of 1973 comes from the

The Red Lodge Clearinghouse, which

is a web-based source of environmental information - to include

information on pertinent environmental law and legislation. This

overview was so thorough and complete that I have chosen to share it

with you in its entirety. However, for a complete analysis and

through overview of the Endangered Species Act, you may want to

review the 2001 report from the Congressional Research Service

entitled "Endangered

Species: Difficult Choices." This provides a very good policy

analysis of this important piece of legislation and how it is

currently fairing.

"The

Endangered Species Act (ESA)

is one of the most powerful of this nation's environmental laws.

Passed in 1973, the act's purpose is to both conserve and

restore species that have been listed by the federal government

as either endangered or threatened (referred to as "listed"

species). The act has several provisions that promote those

goals:

First, the act broadly prohibits anyone from

doing anything that would kill, harm, or harass an endangered

species. Those prohibitions even apply when listed animal

species are on private lands.

Second, federal agencies have a special

obligation to ensure that they do nothing that would harm a

listed species. That obligation significantly affects activities

on federal lands, like grazing, logging, and mining. But it also

means that a federal agency has to assess whether its actions

could affect a listed species before the agency signs off on

projects like a new highway or a dam on non-federal land.

Third, the act tells federal agencies to develop

plans that show how the listed species could be restored—or

"recovered"—so that it no longer needs the act's protections ("delisted").

Key Concepts

Endangered

Species

If an animal or plant species is listed as

"endangered," the species is considered to be in danger of

extinction throughout a large part of its range. It is possible

that a species can be listed as endangered, the highest level of

protection the act provides, in one place but not another. The

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) maintains a

list of

endangered species.

Threatened Species

For a species to be listed as

"threatened," there must be a significant risk that the species

is going to become endangered. Threatened species have a lower

risk of extinction than do "endangered" species. As a result,

state and federal agencies may have some greater flexibility in

how they manage a threatened species than an endangered species.

The USFWS maintains a

list of

threatened species.

Species

Generally

speaking, a "species" is a group of related plants or animals

that can interbreed to produce offspring. Under the ESA, the

word "species" is used more broadly to include any "subspecies"

of fish, wildlife, or plants, and also any "distinct population

segment" of fish and wildlife species that can interbreed.

A

"subspecies" is a subdivision of a species, which is genetically

different from other subspecies and often is geographically

separated. Examples of subspecies are the Mexican and the

Northern Spotted Owls.

A "distinct population segment" is not genetically

different from the species as a whole, but it has very specific

habitat or reproduction habits. An example of a distinct

population segment is a particular group of salmon, which, after

spending their formative years in the ocean, return to the same

mountain stream in which they were born. Thus, the winter run of

the Chinook salmon on the Sacramento River in

California is endangered, and many other runs of

Chinook salmon are threatened, but the spring run of Chinook up

the Clackamas River in Oregon and Washington is neither

endangered nor threatened.

Federal Agencies Responsible for Endangered

species

The Secretary of the

Interior has delegated most of his or her duties under the ESA

to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), which is

responsible for all land-based species. The Secretary of

Commerce has delegated most of his or her responsibilities for

sea life and salmon and steelhead ("anadromous fish" that spawn

in inland waters, migrate to the ocean for several years, and

then return to their spawning grounds) to the National Marine

Fisheries Service (NMFS).

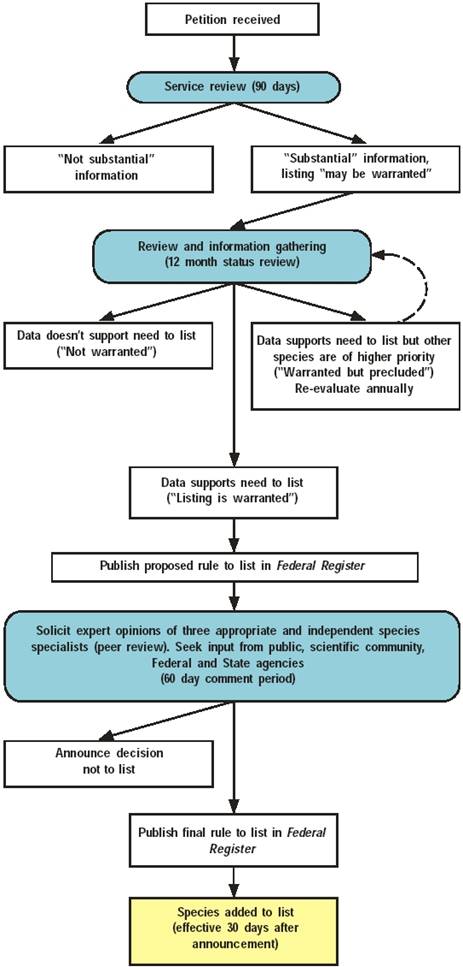

Listing

"Listing" refers to the

process by which a species is formally designated as a

threatened or endangered species. Currently there are more than

1,260 species listed as endangered or threatened under the ESA.

Anyone can submit a

petition to the federal government to have a

species listed. However, that petition must include scientific

information that explains why listing is necessary. The two

federal agencies that receive petitions are the USFWS and the

NMFS. These agencies have a year to evaluate the species for

listing. Either agency can also start the process without a

petition.

After evaluating the species, the agency has

three options:

-

It can agree that a species

should be listed, that is, it concludes that the listing is

"warranted."

-

It can decide that listing is

not justified, that is "not warranted."

-

It can conclude that while

adding the species to the list is justified, other species

have a higher priority; that is, listing is "warranted but

precluded."

Regardless of what decision the agency makes, it

has to publish its decision in the Federal Register and explain

how it reached its decision.

Take, harm

The ESA has broad

provisions to prevent extinction of plant and animal species.

The act prohibits anyone from "taking" a species that has been

listed as threatened or endangered. "Take" can be as simple as

hunting, shooting or killing a listed animal species. It can

also include "harming" a listed species by activities that cause

major changes to habitat and leave an animal unable to feed,

breed, or find shelter.

Critical

habitat

When the federal government lists a species

as endangered, it is also supposed to identify that species'

critical habitat. Critical habitat includes those areas that are

important for the species' survival or recovery and which need

special management. While a designated critical habitat area is

not intended to include all of the potential habitat of the

species, it can include habitat that is not currently occupied

by the species. The federal government is required to use the

best available scientific information in making a decision about

critical habitat. The agency can also consider economics when

deciding what areas should be designated as critical habitat,

although it does not consider economic impacts when it "lists" a

species.

The Secretary of the Interior is not allowed to

designate critical habitat at a military site if the Secretary

decides that the military site has a resource management plan in

place that benefits the affected species. In advocating for this

relatively new provision, the Pentagon claimed that this

provision is necessary to maintain high standards of military

training. that this provision is necessary to maintain high

standards of military training."

Recovery plan

The federal

agency responsible for a listed species must develop a recovery

plan. The plan outlines how it will ensure the species' survival

and restore it to the point where it no longer needs the act's

protections and can be "delisted" or removed from the list of

threatened or endangered species. Examples of recovery efforts

include reintroduction of a species into formerly occupied

habitat (bald eagles), land acquisition (Florida scrub jays),

captive propagation (black-footed ferrets and California

condors), habitat restoration and protection (Aleutian Canada

geese), population assessments and research (Peter's Mountain

mallow), technical assistance for landowners and public

education. In most cases, the USFWS or NMFS works with state

wildlife agencies, user groups, conservationists, and others in

developing such a plan. Because developing and implementing

recovery plans is expensive, the agencies focus their efforts on

species that would most benefit from a plan. While few species

have gone extinct since 1973, only 9 have been "recovered" or

removed from the list because they no longer need the act's

protection. For additional information, see

GAO Report:

Endangered Species: Time and Costs Required to Recover Species

Are Largely Unknown.

Experimental Population

An "experimental population" is a group of individuals of an

endangered species that has been established outside the current

range of the animals. Animals may be reintroduced to their

historical range or to new areas because there is insufficient

habitat in the animals' traditional range. Experimental

populations are considered threatened, not endangered, and

"taking" individual animals is permitted under certain

circumstances. Protections of experimental populations vary

widely, depending on whether the population is considered

"essential" or "nonessential" for species survival. Designation

as a "nonessential experimental population" under the 10(j) rule

of the ESA assures that endangered species are fully protected

from intentional harm, but keeps their presence from restricting

current and future land management practices. Use of this

special designation helped reduce concerns raised by local

communities, landowners and political entities about the

intentional release of endangered species that might enter and

remain on public lands in their region. The reintroduction of

gray wolves to their traditional range in Wyoming and the

California condor to its historic range in Arizona are examples

of experimental populations that are considered "nonessential"

to survival of the species.

Delisting

The process

for "delisting"—removing a species from either the endangered or

threatened list, or changing its status from endangered to

threatened—is similar to the formal listing process. The process

starts with a notice published in the Federal Register.

Delisting may include requirements for special management plans

to help ensure a healthy population in the future. For example,

the states of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming must all have wolf

management plans in place before the gray wolf is delisted.

Process Essentials: Section

7 Consultation

Purpose

Section 7 of the ESA has been at the center of much of the

debate over endangered species protection. Section 7 says that

federal agencies must make sure that none of their actions, or

any action they authorize or fund, is likely either to

jeopardize the existence of a listed species or to damage its

critical habitat. To meet this requirement, federal agencies

considering taking some action—from selling timber to re-issuing

a grazing permit or permitting a new dam—must "consult" with the

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), for land-based species,

or the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), in the case of

sea life or salmon and steelhead. The agencies usually use an

informal process to determine whether formal consultation is

necessary.

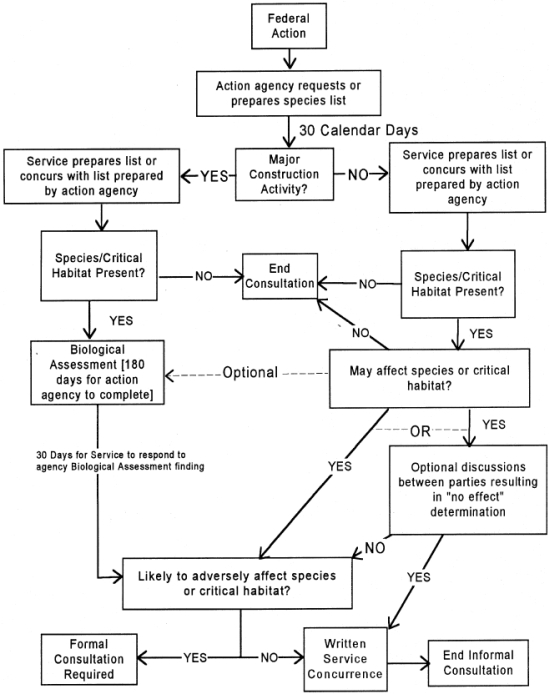

Informal Consultation

Typically, the agency that wants to take an action will

informally consult with USFWS or NMFS, asking whether there are

any proposed or listed threatened or endangered species or

critical habitat in the project area. If the answer is "yes",

then the consulting agency (also know as the "action agency")

must do a

biological assessment (BA) to assess

what impact its action might have on the species or habitat. The

contents of the BA are left to the discretion of the action

agency, but USFWS regulations suggest the following:

-

The results of an on-site

inspection of the affected area;

-

The views of recognized experts

on the species at issue;

-

A review of the literature and

other information;

-

An analysis of the effects of

the action on the species and habitat;

-

An analysis of alternate actions

considered by the action agency.

If the

assessment indicates that there will be no impact, and the USFWS

or NFMS agrees, then informal consultation is over and the

project can go forward. If the BA indicates that the action is

likely to have an effect, then informal consultation is over and

"formal consultation" begins. During the informal consultation,

the USFWS or NMFS may suggest project modifications that the

action agency could take to avoid the likelihood of adverse

impacts. In December 2003 several land management agencies,

USFWS, and NMFS adopted new regulations that exempt National

Fire Plan projects from the informal consultation process. For

more details on these regulations,

see

Controversies: Special Rules for National Fire Plan Consultation

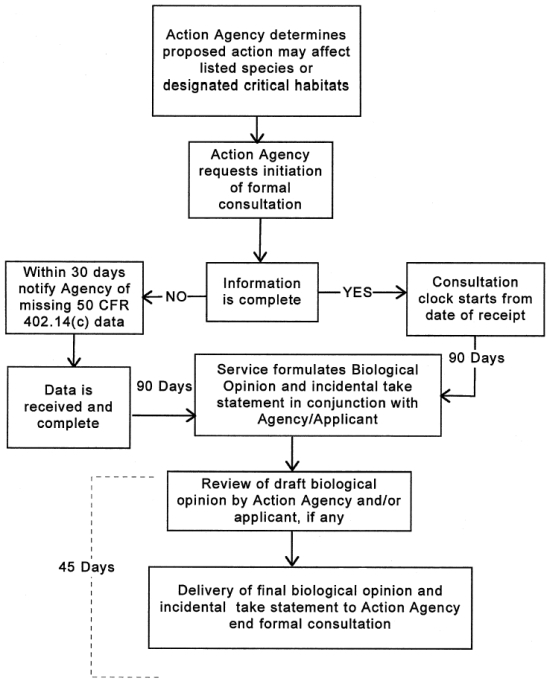

Formal Consultation

If a federal agency informs the USFWS or NMFS that a proposed

action might affect any proposed or listed threatened or

endangered species or critical habitat (typically done as part

of a BA), the agencies begin a formal consultation process. In

this process, the USFWS or NMFS prepares a

biological opinion (BO)—a detailed evaluation of the impacts on

the species and critical habitat—based on the BA produced by the

action agency. The BO thoroughly explains the current status of

the species and describes how the proposed action would affect

the species. The USFWS (or NMFS) can come to one of three

conclusions in its BO:

The agency then has to explain how it concluded

that the action would, or would not, jeopardize the species that

is the subject of the opinion. If the opinion concludes the

action will not adversely affect the species (i.e., a "no

jeopardy" opinion), the action can go forward. If the BO concludes the

action could harm the species, the USFWS or NMFS typically

proposes a set of mitigation measures ("reasonable and prudent"

alternatives) that would allow the activity to proceed. It is

also possible, though rare, that there are no effective

mitigation measures. The practical result of such an opinion is

that the agency either has to revise its proposal, abandon it

altogether, or try to invoke an exemption from the Endangered

Species Committee

(see "Endangered Species Committee Exemptions").

For more information on consultation, see the

USFWS ESA

web site.

Process Essentials: ESA

Tools for the Landowner

Federal Policies & Programs

Participation by private landowners is extremely

important to the protection and recovery of listed species

because many listed species depend on private lands for habitat

during at least part of their lives. Several federal policies

and grant programs are designed to help landowners cooperate in

protection of listed species.

Habitat Conservation Plans (HCP)

A Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) is developed to help protect

species from being harmed by activities on private lands and, at

the same time, to protect private landowners from liability

under the ESA. Sometimes, a private landowner finds out that a

planned project (for example, a housing development) may harm or

"take" an endangered species. By developing an HCP, the

non-federal entity can get the permits it needs to proceed. An

HCP outlines what actions the private party plans to take in

order to minimize, or mitigate, the impact of his or her actions

on the endangered species.

When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)

signs off on an HCP, it generally gives permission to the

private party to "take" endangered species as an incident to the

development activity (issues an "incidental take permit"). Plans

can be developed for listed threatened or endangered species and

for other rare species. Including unlisted species in an HCP can

provide for early protection for the species that might keep it

from needing to be listed in the future. For more information on

HCPs, see

the USFWS

Habitat Conservation Planning website.

The Habitat Conservation Planning Process

According to Peter

Aengst, et al., (1997) of the University of MIchigan:

"The

planning process has three general stages: development,

approval, and implementation. The development of an HCP

typically requires significant scientific baseline

collection and analysis, often conducted by outside

consultants hired by the applicant. The whole process can

take many years and cost millions of dollars. Usually,

district-level FWS or NMFS staff assist in the applicant's

development of the HCP by providing clarification,

scientific information, and feedback. For many large or

complex HCPs, a steering committee representing affected

stakeholders and scientific and agency interests is formed.

In the

development stage, parties also negotiate the terms of the

agreement. In return for allowing an incidental take of a

species, the parties agree to pursue specific management

protections for the species. Almost all HCPs share a basic

central strategy of identifying and protecting certain high

value habitat areas. In some cases, the landowner sets aside

a portion of his or her own land for conservation purposes;

in others, the landowner or independent parties (e.g.,

private land trusts; local, state, or federal government

entities) purchase the habitat conservation areas. Local

zoning restrictions have also been used to protect

designated areas (Beatley 1994). In addition to these land

protections, HCPs can also include other mitigation actions,

such as public education campaigns, habitat restoration,

land-use restrictions on nearby public lands, control of

exotic species or predation, captive breeding, or changes to

the design or density of landowners' projects.

The

approval stage of the HCP planning process involves both

internal agency analysis and external public review. The

applicant usually submits four documents for agency

approval: (1) a completed permit form which requests the

specified amount and rate of incidental take; (2) the HCP,

which includes the scientific information and details of the

mitigation plan; (3) an implementation agreement which

serves as a binding contract and details how the elements of

the plan will be carried out, paid for, and monitored; and

(4) the appropriate National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

documentation (i.e., environmental assessment or

environmental impact statement). The agency in turn will

amend the NEPA documents if necessary and publish notice of

the HCP and a minimum 30-day public comment period in the

Federal Register. If the agency approves the HCP, it

issues the applicant an ITP. This permit action qualifies as

a federal agency action; thus, the agency must engage itself

in a "self-consultation" process to evaluate whether the

proposed action is in compliance with Section 7 of the ESA

(50 Federal Register 39685, Sept. 30, 1985). State

endangered species laws and environmental reviews, as well

as local zoning or planning regulations, may require

additional documentation or public review.

Implementing the HCP involves carrying out the prescribed

mitigation actions, collecting funds, and monitoring take

levels and overall species impacts. Funding for

implementation of the HCP can take many forms and often

involves some combination of federal, state, local, and

private sources, such as per-unit fees on new development,

community-wide taxes, contributions from participating

groups (e.g., The Nature Conservancy), state wildlife funds,

issuance of city bonds, and Federal Land and Water

Conservation Fund appropriations. Monitoring

responsibilities for approved HCPs are usually jointly

shared by the applicant and the FWS or NMFS and often

involve preparation of periodic reports documenting the

amount of development that has occurred, number and type(s)

of listed species taken, and the amount of money generated

and spent to date.

The

Growth of HCPs

Landowners and the agencies initiated relatively few HCPs in

the years following the creation of the Section 10(a)

incidental take provisions in 1982. Traditionally, the

agencies focused their efforts on those projects or actions

that included federal lands or some federal permit approval.

Since the Section 10 process is voluntary, most potential

applicants chose not to participate and appear to have

relied on lax enforcement of the Section 9 take prohibitions

on private property (Houck 1993). Moreover, the HCP process

was historically viewed as procedurally difficult, costly,

plagued with delays, and risky in terms of regulatory

assurances.

Habitat

conservation planning, however, has changed dramatically in

recent years. Growing scientific recognition of the role of

private lands for endangered species recovery and the

landmark 1981 District Court ruling in Palila v. Hawaii

Department of Land and Natural Resources (639 F.2d 495,

9th Cir., 1981) both contributed to making Section 9 "a

major force for wildlife conservation and a major headache

to the development community". Indeed, during the last

decade there has been a significant rise in disputes

concerning Section 9's application to private property.

Perhaps

more importantly, the Clinton Administration has made

several administrative changes in its ESA policies that have

increased the incentive for landowners to engage in the HCP

planning process and led to a dramatic increase in the

number of landowners applying for and receiving approval for

HCPs. Indeed, in an effort to encourage the broader

application of HCPs and to deflate Congressional efforts to

weaken the ESA, the Clinton Administration has sought to

make Section 10 and HCPs "one of the ESA's most important

and innovative conservation programs".

The

result has been a dramatic increase in the number and scope

of HCPs that have been proposed and approved. Prior to 1994

the FWS had approved a total of only 20 HCPs. However, after

the Clinton Administration's efforts to streamline the

planning process and increase landowner incentives to

participate, the FWS approved 174 new plans between 1994 and

1996. At the end of 1996 there were approximately 200 HCPs

at some stage of preparation, and the FWS expects to work on

as many as 400 during FY 1998. In addition, the scale and

scope of HCPs have increased dramatically in recent years.

The FWS and NMFS report that the majority of HCPs developed

prior to 1995 were of less than 1,000 acres in area while

HCPs in development in 1996 included 25 that exceed 10,000

acres, 25 that are more than 100,000 acres, and 18 that

exceed 500,000 acres (FWS 1997b). By September 1997, the U.

S. Department of Interior expects that more than 18.5

million acres of private land and over 300 species will be

covered by HCPs."

No Surprises Policy

In an effort to encourage private property owners to protect

endangered species and their habitat, federal agencies have

developed a "no surprises" policy that can be written into an

HCP. This policy promises the private landowner that if he or

she develops an HCP in good faith and the federal agency later

concludes that additional measures (e.g., protection of more

land) are needed to protect the endangered species, the federal

agency cannot require the private landowner to do anything more

than what he or she already has committed to do. In other words,

the private party who commits to helping to conserve an

endangered species doesn't have to be worried about a "surprise"

down the road.

Permit Revocation Rule

When the

USFWS approves an HCP plan, they issue an "incidental take"

permit that prevents the private property owner from being

prosecuted if an endangered species is incidentally killed or

injured during the development. Because several conservation

groups and an Indian tribe were concerned that there would be no

recourse for a species is peril of extinction, the USFWS created

a new rule, the

permit

revocation rule

which allows the agency to revoke incidental take permits,

despite the "no surprises" policy, when incidental takes would

"appreciably reduce the likelihood of survival and recovery of

the species in the wild." For more information on the

controversial and litigious history of the permit revocation

rule and "no surprises" policy, see

Judge puts

hold on 'No Surprises' rule

and

Court

dismisses FWS appeal over 'No Surprises.'

For more information on Incidental Take Permits, see

Process

Essentials: ESA Exceptions or Exemptions.

Conservation Banks

One way developers can fulfill a promise to mitigate damage to a

species is through the use of conservation banks. Conservation

banks are lands acquired and managed for specific endangered

species. The lands are usually protected permanently by

conservation

easements.

Once a conservation bank is established, the "banker" may sell a

fixed number of

"mitigation

credits" to developers to offset adverse effects of the

developer's project on a species. These effects may include

destruction of some of the species' habitat or disturbance of

the species from increased activity in the area of the

development.

The banks operate on the theory that

species conservation will be most effective, and people will be

most willing to participate in conservation efforts, if everyone

benefits from conserving species. Conservation banking benefits

all parties:

-

Species benefit from protection

of much-needed, secure habitat.

-

Developers benefit because they

can go forward with the development and receive an

incidental take permit. Buying credits is easier, and

usually more economical, for the developer than developing

an individual mitigation project.

-

Owners/managers of the

conservation banks benefit monetarily through the

developers' purchase of mitigation credits.

Safe Harbor Agreements

Some private landowners are unwilling to adopt conservation

measures that improve habitat for threatened or endangered

species on their land for fear that their future development

decisions would then be limited by the presence of the

endangered species. Unfortunately, that restricts the amount of

privately owned land available for use by threatened and

endangered species. Safe Harbor Agreements are designed to get

around this conflict. The agreements assure landowners who

voluntarily improve habitat for endangered species that their

future land development won't be limited if they attract

endangered species to their property or increase their numbers.

Title V of the Healthy Forests Restoration Act requires the

Secretary of Agriculture to establish a healthy forests reserve

program for the purpose of restoring and enhancing forest

ecosystems to improve biodiversity, enhance carbon

sequestration, and to promote the recovery of threatened and

endangered species. The program provides both funding and

technical assistance to landowners who volunteer to enroll their

land. Safe harbor agreements and other assurances will be made

with the landowners as part of the program. For more information

on the reserve program, see

Healthy

Forests Restoration Act: Title 5.

Candidate Conservation Agreements

with Assurances

Candidate Conservation Agreements

with Assurances (CCAA) are agreements made between the USFWS or

NMFS and landowners. These formal agreements are created to

address the specific conservation needs of a particular species,

in hopes of keeping it off of the endangered or threatened

species lists. The private parties to these agreements

voluntarily commit to manage their land and water to decrease

current and future threats to a species, so that the population

of that species may thrive without federal protection. In

exchange, the owners receive assurances from the agency, much

like the "no surprises policy" of an HCP, that they will not be

required to do more than what they agreed to when they entered

the agreement. In order to receive the assurances, the

landowner's management activities must significantly contribute

to eliminating the need to list the covered species. Species

covered in a CCAA may include both animals and plants, and

either candidates for listing or species that have already been

proposed as threatened or endangered.

Process Essentials:

Categories of Protection

Categories of

Species

Not all species are created equal under the

ESA. Different categories of species receive different

protection. There are three types of species in the ESA listing

process:

Protection under the ESA also differs between

plants and animals, and between species listed with or without a

critical habitat designation.

Listed

Species: Endangered or Threatened

A "listed species"

is any species of fish, wildlife, or plant that has been

determined, through the full, formal ESA listing process, to be

either threatened or endangered. Endangered species receive the

full protections of the ESA—protection from "takings" and other

specific prohibited acts (like commercial trade in the species),

designations of critical habitat, requirements for Section 7

consultations, and recovery plans. Threatened species are

protected with critical habitat designations, Section 7

consultations, and recovery plans, but they are only protected

from takings and other prohibited acts if the USFWS or the NMFS

decides it is necessary to do so.

Proposed Species

A "proposed species" is any species

of fish, wildlife, or plant that has been formally proposed for

listing as either a threatened or endangered species under the

ESA. The USFWS or the NMFS publishes a proposal to list the

species—a "proposed rule"—in the Federal Register, prior to

making a final decision to list the species by publishing a

"final rule." Proposed species are not protected from "takings"

or other prohibited acts, but the USFWS or NMFS can propose

critical habitat for them. Federal agencies must follow the

Section 7 consultation process for proposed species in order to

avoid jeopardizing the species or destroying its proposed

critical habitat.

Candidate

Species

"Candidate species" are plants and animals on a

"waiting list" for threatened or endangered status. This means

the USFWS or NMFS has sufficient information to list these

species, but other, higher-priority species have to be listed

first—the agency has concluded that a listing is "warranted but

precluded." Candidate species are not legally protected under

the ESA, but USFWS and the NMFS encourage partnerships to

protect them because effective conservation might reverse their

decline and ultimately eliminate the need for ESA protection.

Plants and Animals

Under the ESA, plants and animals

have the same protections from most

"prohibited acts"—import-export, possession, transport, or

commercial dealing in the species. They have similar protections

from more direct harm: it is illegal to kill, harm, harass, or

even hunt (collectively called "take") listed animal species;

listed plants cannot be picked, dug up or destroyed. Animals are

protected from these actions on all lands, but plants are only

protected on federal lands unless there is a state law that also

protects them.

Species listed with or without a critical habitat

designation

Only about 12 percent of listed species have a

designated critical habitat area. According to the USFWS, a

critical habitat designation affords little extra protection to

most listed species. The agency has, therefore, used its limited

staff and funding to list more species rather than spending

resources on designating critical habitat. In some cases, the

agency decides not to designate critical habitat in order to

better protect the species. Sometimes a critical habitat

designation may do more harm than good because of public

hostility to the designation, because it makes a species like a

rare cactus easier to locate, or because of misconceptions about

the lack of value to the species of land outside the designated

critical area.

Having a critical habitat designation

only gives extra protection to a species if there is a federal

agency involved, and then only under certain circumstances. If

there is no federal agency involved in a project (for example,

when a landowner builds a housing development on private land

without federal funding or a federal permit), there is no extra

protection for the species if the land has been designated as

critical habitat. If a federal agency is involved (e.g., in

issuing a permit for the housing development), a critical

habitat designation may make a difference during the Section 7

consultation process.

In a Section 7 consultation, the

agency must consult with the USFWS or NMFS to ensure that its

actions will not jeopardize the survival of the species or

destroy or adversely modify critical habitat. In most places,

ensuring that its actions won't jeopardize survival of the plant

or animal, provides at least as much protection as protecting

the species' critical habitat. Protecting its critical habitat

could provide extra protection to the species if the land being

developed were currently "unoccupied" by the species, but were

nonetheless important to its future survival.

Process

Essentials: ESA Exceptions or Exemptions

Otherwise Prohibited Activities

The ESA provides strong protection for threatened and

endangered species, but a few exceptions to the law are

available through the USFWS, the NMFS, or the Endangered Species

Committee after following a formal application process. These

exceptions/exemptions allow individuals or agencies to do a

variety of things that are otherwise prohibited, like

transporting or even causing the death of a listed animal,

without fear of prosecution. The most common exceptions are for:

Scientific Purposes, Including Experimental Populations

The USFWS and the NMFS can issue permits for scientific purposes

or for projects that enhance the propagation or survival of the

species. For example, the agency might issue a permit for a

project designed to establish or maintain a new population of

wolf, lynx, or condor. While the intention of the recovery team

would be to better understand the species to help it survive,

biologists might harass an animal while trying to capture it and

might even inadvertently kill it in transport. Or the team might

need to intentionally kill it for a special medical test or

because an individual from an experimental population threatens

livestock.

Incidental takings

USFWS or

NMFS can issue permits to either federal agencies or private

landowners for taking a species (harming or killing it or

destroying its habitat) if the taking is "incidental to," and

not the purpose of, the action. To apply for this kind of

permit, the individual, corporation, or state or local

government has to prepare a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP). The

permit applicant must describe actions he or she will take to

minimize and mitigate impacts to the species. The applicant must

also justify why there is no reasonable way of completely

avoiding a potential taking.

Endangered Species Committee

exemptions

Federal agencies have a special duty under the

ESA to make sure that their actions don't harm threatened or

endangered species or their critical habitat. If an agency

completes the Section 7 consultation process and is told that

its proposed action is likely to jeopardize a species or damage

its habitat, the agency can apply for an exemption that would

enable it to go ahead with its proposed action (e.g., building a

visitor center, operating a dam, or issuing just about any kind

of permit or license). The project permitee or licensee, or the

governor of the state affected by it, can also apply for the

exemption. The final decision on whether to grant an exemption

is made by the Endangered Species Committee (the so called "god

squad") after following an elaborate public process. The

seven-member committee includes several cabinet members, the

chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), and

other high-level appointees.

When granting an exemption, the committee must

develop reasonable mitigation and enhancement measures to

minimize the negative impacts of the agency's action. The

committee has been convened only three times—for the snail

darter fish in Tennessee, the spotted owl in Oregon and the

whooping crane in Nebraska."

|