| Home Page | Case Studies | Web Resources | Schedule |

Sessions

|

ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AND LAW

|

Return to Session 8: Trade and Environment

NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement)

Implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) began on January 1, 1994. This agreement will remove most barriers to trade and investment among the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Under the NAFTA, all nontariff barriers to agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico were eliminated. In addition, many tariffs were eliminated immediately, with others being phased out over periods of 5 to 15 years. All agricultural provisions will be implemented by the year 2008. For import-sensitive industries, long transition periods and special safeguards will allow for an orderly adjustment to free trade with Mexico.

The agricultural provisions of the U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement, in effect since 1989, were incorporated into the NAFTA. Under these provisions, all tariffs affecting agricultural trade between the United States and Canada, with a few exceptions for items covered by tariff-rate quotas, will be removed by January 1, 1998.

Mexico and Canada reached a separate bilateral NAFTA agreement on market access for agricultural products. The Mexican-Canadian agreement eliminated most tariffs either immediately or over 5, 10, or 15 years. Tariffs between the two countries affecting trade in dairy, poultry, eggs, and sugar are maintained."

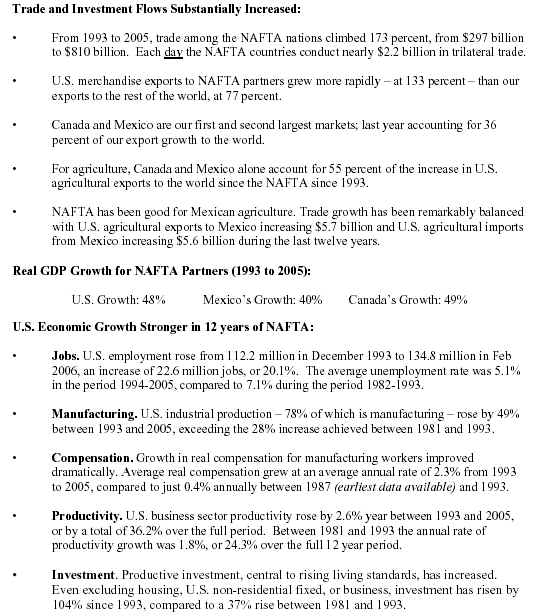

The table below illustrates the net effect of NAFTA as of 2006:

NAFTA Environmental Provisions

"Environmental issues emerged early in NAFTA negotiations, particularly in the context of liberalizing trade and investment rules between the United States and Mexico. One question concerned how NAFTA might affect one country's more stringent standards, and whether these standards could be challenged successfully as non-tariff trade barriers. Conversely, the question was raised whether a country's weaker environmental protection measures or their ineffective enforcement would create a competitive advantage and provide an added incentive for businesses to relocate production to the least regulated country. Many in Congress expressed concern that, although Mexican regulations were becoming more like U. S. regulations, Mexico had many fewer requirements and historically lax enforcement. A related concern was that anticipated industrial growth in the U.S.-Mexico border region would exacerbate the severe pollution problems already present. Trade officials countered that environment was not a customary trade matter and that NAFTA talks were not the proper forum for resolving environmental issues. Nonetheless, the level of concern over these issues in Congress during NAFTA negotiations prompted the Bush Administration respond to them.

While not a new issue, the question of whether a country's stricter environmental measures could be found to pose non-tariff trade barriers received an unprecedented level of attention during the NAFTA debate. Ultimately, negotiators included language to conditionally protect a party's stricter environmental, health, and safety standards for products and produce (provided that, among other things, such measures are scientifically based). Other related NAFTA provisions place the burden of proof that an environmental measure is inconsistent with NAFTA on the party challenging the measure, encourage upward harmonization of standards, and encourage parties to integrate environmental protection and sustainable development into economic decision-making. NAFTA also includes hortatory language to discourage parties from lowering standards to encourage investment. The agreement's standards provisions generally do not affect a country's ability to determine its own levels of protection for manufacturing and other process standards (such as air and water pollution controls, and resource harvesting practices); however, the investment provisions do allow companies to challenge environmental measures that are viewed as harming their investments.

NAFTA also addresses its relationship to multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs). It identifies three trade-related MEAs that may take precedence over NAFTA where implementation conflicts arise, provided that the MEA is implemented in the least NAFTA-inconsistent manner. The listed agreements include the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer; the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal; and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). U.S.-Mexico and U.S.-Canada bilateral waste-trade agreements also are included, and the parties may add others.

Despite the inclusion of the above provisions, some in Congress remained concerned that NAFTA's effect on specific standards or environmental laws could be unpredictable. As with other trade agreements, NAFTA comprises a mix of rights, obligations, and disciplines, and there is room for debate as to which provisions might prevail in particular cases. For example, an emerging issue involves the potential effect that NAFTA may have on state and federal environmental protection efforts because some investors have challenged domestic environmental measures as constituting a form of expropriation for purposes of the NAFTA investment chapter."

NAFTA Environmental Side Agreement:"A matter not addressed in the NAFTA text was whether lax enforcement of environmental laws in Mexico would provide an added incentive for U.S. industries to relocate, and thus increase U.S. job losses, reduce the competitiveness of U.S. products, and increase border-area pollution. Many in Congress called for a side agreement that included an enforcement mechanism to address failures to enforce environmental laws. Others were troubled at the prospect of further environmental provisions, particularly any that might increase the regulatory burden on businesses. Opponents of a side agreement argued that NAFTA-related economic growth would increase Mexico's resources available for environmental protection, and that NAFTA would increase cooperation on environmental matters throughout North America. Congressional support for NAFTA remained uncertain. Candidate William Clinton endorsed NAFTA but promised to negotiate side accords on environmental and labor issues.

In September 1993, the three NAFTA governments signed the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC), which includes provisions to address a party's failure to enforce environmental laws. The side agreement's objectives cover a range of goals including avoiding the creation of trade distortions or new trade barriers, enhancing compliance with, and enforcement of, environmental laws and regulations, and fostering environmental protection and pollution prevention."According to the U.S. Department of Commerce's International Trade Commission (ITC), "[t]he North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC), which was approved as a side agreement to NAFTA, ensures that trade liberalization and efforts to protect the environment are mutually supportive. The key goals of the NAAEC are to foster the protection and improvement of the environment, improve conservation efforts, promote sustainable development, and increase cooperation on and enhanced enforcement of environmental laws and policies. The NAAEC created three separate bodies to support these objectives:

the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC): "The Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) is an international organization created by Canada, Mexico and the United States under the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC). The CEC was established to address regional environmental concerns, help prevent potential trade and environmental conflicts, and to promote the effective enforcement of environmental law. The Agreement complements the environmental provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)."

the Border Environment Cooperation Commission (BECC): "The BECC was established in November 1993 in the context of the parallel agreements under the Free Trade Treaty. It is a bi-national agency set up by the Mexican and United States governments to identify, evaluate and certify environmental infrastructure projects within a broad process of community participation. It works in the border strip which extends 100 kilometers to the north and 100 kilometers to the south of the border between Mexico and the United States. Its priority action areas are drinking water, sewerage, sanitation and municipal solid-waste management."

the North American Development Bank (NADBank): "The North American Development Bank (NADB) and its sister institution, the Border Environment Cooperation Commission (BECC), were created under the auspices of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to address environmental issues in the U.S.-Mexico border region. The two institutions initiated operations under the November 1993 Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the United Mexican States Concerning the Establishment of a Border Environment Cooperation Commission and a North American Development Bank (the “Charter”).

However, in response to growing concern on both sides of the border that a large portion of the NADB's resources were going unused, despite the many urgent infrastructure and environmental needs in the border region, the NADB Board of Directors initiated discussions on expanding the Bank’s financing activities in June 2000. These discussions gave rise to a broad set of reform initiatives, some of which required changes to the original BECC-NADB Charter. Following passage of the necessary U.S. and Mexican legislation, an amended Charter went into force on August 6, 2004.

Established in 1994 with headquarters in San Antonio, Texas, the NADB is a bilaterally-funded, international organization, capitalized and governed equally by the United States and Mexico for the purpose of financing environmental infrastructure projects along their joint border. Its mission is to serve as a binational partner and catalyst in communities along the U.S.-Mexico border in order to enhance the affordability, financing, long-term development and effective operation of infrastructure that promotes a clean, healthy environment for the citizens of the region.

The NADB can provide financial assistance to public and private entities involved in developing environmental infrastructure projects in the border region. Potable water supply, wastewater treatment and municipal solid waste management form the core sectors of the Bank’s activities and are its primary focus. However, assistance can also be provided in other areas—such as air quality, clean energy and hazardous waste—where sponsors are able to demonstrate tangible health and/or environmental benefits for residents living in the area.

The NADB is authorized to serve communities in the U.S.-Mexico border region, which extends 2,100 miles from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean. Eligible communities must be located within 100 kilometers (about 62 miles) north of the international boundary in the four U.S. states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California and within 300 kilometers (about 186 miles) south of the border in the six Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Sonora, and Baja California."

The CEC serves all three NAFTA Parties, while the BECC and the NADBank operate under a bilateral agreement between the U.S. and Mexico signed by the Presidents of the United States and Mexico in November 1993. This bilateral agreement created an environmental infrastructure program that gives communities on the U.S.-Mexico border a greater role in determining needs and how to fill them, and incorporating a mix of federal, state, local, and private-sector funding. The institutions' work is primarily directed to projects for wastewater and drinking water treatment, and projects for the management of municipal solid waste."

"There are over one million Mexicans working in over 3,000 maquiladora manufacturing or export assembly plants in northern Mexico, producing parts and products for the United States. Mexican labor is inexpensive and courtesy of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement), taxes and custom fees are almost nonexistent, which benefit the profits of corportations. Most of these maquiladora lie within a short drive of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Maquiladoras are owned by U.S., Japanese, and European countries and some could be considered "sweatshops" composed of young women working for as little as 50 cents an hour, for up to ten hours a day, six days a week. However, in recent years, NAFTA has started to pay off somewhat - some maquiladoras are improving conditions for their workers, along with wages. Some skilled workers in garment maquiladoras are paid as much as $1-$2 an hour and work in modern, air-conditioned facilities.

Unfortunately, the cost of living in border towns is often 30% higher than in southern Mexico and many of the maquiladora women (many of whom are single) are forced to live in shantytowns that lack electricity and water surrounding the factory cities. Maquiladoras are quite prevalent in Mexican cities such as Tijuana, Ciudad Juarez, and Matamoros that lie directly across the border from the interstate highway-connected U.S. cities of San Diego (California), El Paso (Texas), and Brownsville (Texas), respectively.

Maquiladoras originated in Mexico in the 1960s along the U.S. border. In the early to mid-1990s, there were approximately 2,000 maquiladoras with 500,000 workers. In just a few years, the number of plants has almost doubled and the number of workers has more than doubled. Maquiladoras primarily produce electronic equipment, clothing, plastics, furniture, appliances, and auto parts and today eighty percent of the good produced in Mexico are shipped to the United States. Ninety percent of the goods produced at maquiladoras are shipped north to the United States.

While some of the companies that own the maquiladoras have been increasing their workers' standards, most employees work without even knowledge of unions (a single official government union is the only one allowed) and some work up to 75 hours a week. Some maquiladoras are responsible for significant industrial pollution and environmental damage to the northern Mexico region.

Competition from China has weakened the allure of maquiladoras in recent years and some report that more than 500 plants have closed since the beginning of the decade, causing a loss of several hundred thousand jobs. China is bolstering its status as the world's cheap assembly export location."

According to the watchdog group Public Citizen, NAFTA " includes an array of new corporate investment rights and protections that are unprecedented in scope and power. NAFTA allows corporations to sue the national government of a NAFTA country in secret arbitration tribunals if they feel that a regulation or government decision affects their investment in conflict with these new NAFTA rights. If a corporation wins, the taxpayers of the "losing" NAFTA nation must foot the bill. This extraordinary attack on governments' ability to regulate in the public interest is a key element of the proposed NAFTA expansion called the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA).

NAFTA's investment chapter (Chapter 11) contains a variety of new rights and protections for investors and investments in NAFTA countries. If a company believes that a NAFTA government has violated these new investor rights and protections, it can initiate a binding dispute resolution process for monetary damages before a trade tribunal, offering none of the basic due process or openness guarantees afforded in national courts. These so-called "investor-to-state" cases are litigated in the special international arbitration bodies of the World Bank and the United Nations, which are closed to public participation, observation and input. A three-person panel composed of professional arbitrators listens to arguments in the case, with powers to award an unlimited amount of taxpayer dollars to corporations whose NAFTA investor privileges and rights they judge to have been impacted."To date, one of the most prominent court cases involving Chapter 11 of NAFTA is Methanex Corporatioin v. United States. According to the U.S. Department of State,

"Methanex Corporation, a Canadian marketer and distributor of methanol, submitted a claim to arbitration under the UNCITRAL rules on its own behalf for alleged injuries resulting from a California ban on the use or sale in California of the gasoline additive MTBE. Methanol is an ingredient used to manufacture MTBE.

Methanex contended that a Califiornia Executive Order and the regulations banning MTBE expropriated parts of its investments in the United States in violation of Article 1110, denied it fair and equitable treatment in accordance with international law in violation of Article 1105, and denied it national treatment in violation of Article 1102. Methanex claimed damages of $970 million.

A hearing on jurisdiction and admissibility was held in July 2001. On August 7, 2002, the Tribunal issued a First Partial Award on issues of jurisdiction and admissibility. A hearing on the merits was held in June 2004.

On August 9, 2005, the Tribunal released the Final Award, dismissing all of the claims. The Tribunal also ordered Methanex to pay the United States' legal fees and arbitral expenses in the amount of approximately $ 4 million."Another prominent case is that of Ethyl Corp. v. Canada. According to Canadian documents, this 1997 dispute between Canada and Ethyl Corporation, a Virginia-based U.S. corporation with a Canadian subsidiary, began when the U.S. company alleged " that a Canadian statute banning imports of the gasoline additive MMT for use in unleaded gasoline breached Canada's obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement. In response to a similar challenge launched by three Canadian provinces, a Canadian federal-provincial dispute settlement panel, established under the Agreement on Internal Trade, subsequently found against the federal measure. Accordingly, Canada and Ethyl settled all outstanding matters, including the Chapter Eleven claim.

Current and previous arbitrations emanating from NAFTA's Chapter 11 which involves the United states are presented in the table below.

Current Arbitrations to which the United States of America is a Party

Softwood Lumber Consolidated Proceedings

In 2005, the United States requested that the three separate cases filed by Canadian softwood lumber producers be consolidated pursuant to NAFTA Article 1126. On September 7, 2005, the Tribunal appointed to consider this request ordered that the three cases be consolidated on the basis that all the claims shared similar questions of law and fact.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to the consolidated proceedings can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site..

Canfor Corporation v. United States of America

Canfor Corporation, a Canadian forest products company, filed a Notice of Arbitration in July 2002 alleging that certain antidumping, countervailing duty and material injury determinations the United States has levied on softwood lumber imports breached their obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.

Open Hearings

Kenex Ltd. v. United States of America

Kenex Ltd., a Canadian company, manufactures, markets and distributes industrial hemp products, including whole hemp grain, hemp grain derivatives, hemp fibre and certified hemp seed throughout North America. Kenex Ltd submitted a Notice of Arbitration in August 2002 alleging that the United States Drug Enforcement Agency and the Office of National Drug Control Policy implementation of a ban prohibiting the trade of industrial hemp products breached the United States' obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.

Glamis Gold Ltd. v. United States of America

Glamis Gold Ltd., a publicly-held Canadian corporation engaged in the mining of precious metals, submitted a claim to arbitration in December, 2003 on behalf of its enterprises Glamis Gold, Inc. and Glamis Imperial Corporation for alleged injuries relating to a proposed gold mine in Imperial County, California. Glamis claims that certain federal government actions and California measures with respect to open-pit mining operations breached the United State's obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.Tembec Inc. v. United States of America

Tembec Incorporated, a Canadian forest products company, filed a Notice of Arbitration in December 2003 alleging that certain antidumping, countervailing duty and material injury determinations the United States has levied on softwood lumber imports breached their obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.

Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. v. United States of America

Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd., a Canadian corporation involved in the manufacture and sale of tobacco products, along with Jerry Montour, Kenneth Hill and Arthur Montour filed a Notice of Arbitration in March 2004. The claim alleges that a 1998 settlement agreement between various U.S. state attorney generals and the major tobacco companies and certain state legislation that partially implements the settlement breached the obligations of the United States under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.

Terminal Forest Products Ltd. v. United States of America

Terminal Forest Products Ltd., a Canadian forest products company, filed a Notice of Arbitration in March 2004 alleging that certain antidumping, countervailing duty and material injury determinations the United States has levied on softwood lumber imports breached their obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.

Cattlemen for Fair Trade v. United States of America

As of March 16, 2005, members of the Canadian Cattlemen for Fair Trade have filed 107 Notices of Arbitration alleging that the United States violated its NAFTA Chapter Eleven obligations by closing the border to the importation of Canadian cattle after the discovery in 2003 of a case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or mad cow disease) in a cow in Alberta.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.

Previous Arbitrations to which the United States of America is a Party

Methanex Corp. v. United States of America (Discussed Previously)

Methanex Corporation, a Canadian marketer and distributor of methanol, submitted a claim in June 1999 alleging that the U.S. is in breach of its obligations under Chapter Eleven through California's enactment of a ban on the use or sale in California of the gasoline additive MTBE. Methanol is an ingredient used to manufacture MTBE.

On August 9, 2005, the Methanex Tribunal issued an award dismissing all claims against the United States.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site

Open Hearings

Mondev International Ltd. v. United States of America

Mondev International Ltd.(Mondev), a Canadian real-estate development corporation, which owns and controls a Massachusetts limited partnership, Lafayette Place Associates, submitted a claim in September 1999 alleging that a decision by the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts and from Massachusetts state law breached the United State's obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

On October 11, 2002, the Mondev Tribunal issued an award dismissing all claims against the United States.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.

ADF Group Inc. v. United States of America

ADF Group Inc. ("ADF"), a Canadian corporation that designs, engineers, fabricates and erects structural steel, filed a claim, in July 2000, on its own behalf and on behalf of ADF International Inc., its Florida subsidiary. ADF alleged that the federal Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1982 and the Department of Transportation's implementing regulations, which require that federally-funded state highway projects use only domestically produced steel, breach the United State's obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

The Tribunal issued their Award on January 9, 2003, which rejected all of ADF's claims and ordered that each party bear its own expenses and share on a fifty-fifty basis the costs of the proceeding.

A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site.

The Loewen Group Inc. and Raymond L. Loewen v. United States of America

The Loewen Group, Inc. ("TLGI"), a Canadian corporation involved in the death-care industry, and Raymond L. Loewen, its chairman and CEO at the time of the events at issue, filed a claim in July 1998 alleging that the conduct of a civil case in Mississippi and the reduction of bond required for leave to appeal breached the United State's obligations under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

On June 26, 2003, the Loewen Tribunal issued an award dismissing all claims against the United States.A copy of the legal documents pertaining to this case can be found on the U.S. Department of State web site

Sessions

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14