IMF: International Monetary Fund:

"The IMF was created to promote internatioal monetary cooperation; to

facilitate the expansion and balanced growth of internatioal trade; to

promote exchange stability; to assist in the establishment of a multilateral

system of payments; to make its general resources temporarily available to

its members experiencing balance of payments difficulties under adequate

safeguards; and to shorten the duration and lessen the degree of

disequilibrium in the international balances of payments of members."

"The International Monetary

Fund (IMF or Fund) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and

Development (IBRD or World Bank) were both established at the United Nations

Monetary and Financial Conference, held at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, on

July 1-22, 1944. The two were created to oversee stability in international

monetary affairs and to facilitate the expansion of world trade. Membership

in the World Bank requires membership in the IMF, and they are both

specialized agencies of the United Nations. The World Bank was given domain

over long-term financing for nations in need, while the IMF's mission was to

monitor exchange rates, provide short-term financing for balance of payments

adjustments, provide a forum for discussion about international monetary

concerns, and give technical assistance to member countries. These functions

are still generally true of both organizations, although the policies

determining how they are carried out have been modified and amplified over

time.

The Fund's legal authority is based on an international treaty called

the Articles of Agreement (Articles or the Agreement) which came into

force in December 1945. The first Article in the Agreement outlines the

purposes of the Fund and, although the Articles have been amended three

times in the course of the last 47 years prior to 1998, the first

Article has never been altered.

The IMF started financial operations on March 1, 1947. Drawings on Fund

reserves were made by 11 countries between 1947 and 1948, although there

were no drawings in 1950 and very few in the following years. During

this time the Fund worked on its drawings policies. One outcome was the

stand-by arrangements, established in 1952, modified in 1956, and

reviewed periodically since then. Stand-by arrangements provide a

procedure for drawing on Fund resources with conditions based on a

structural adjustment program for the borrower country. Stand-by

arrangements became the model for other lending procedures designed by

the Fund to meet the needs of its members.

By the mid-1970s, the Fund found itself becoming more of a lending

institution than originally envisioned. The Fund's ability to meet the

needs of its members was tested when the Organization of the Petroleum

Exporting Countries (OPEC) quadrupled the price of crude oil in

1973-1974. Prices were increased again in 1979 and in 1980. This altered

the international flow of funds as the OPEC countries' monetary reserves

accumulated rapidly. At the same time, the industrial countries

experienced strong inflationary pressures. These pressures were

addressed by an increase in interest rates and a reduction of imports.

This resulted in balance of payments deficits for many of the developing

countries, which were paying more for oil, paying higher interest rates

on the loans from the industrial countries, and finding reduced markets

for their exports. In response to this situation, the IMF created an Oil

Facility in 1974, and enlarged it in 1975, to aid members in balance of

payments difficulties. In addition, an Oil Facility Subsidy Account was

established for the poorest countries to alleviate the cost of borrowing

under the Oil Facility. During the 1970s, although the oil price shocks

placed more countries in balance of payments difficulties and forced

many of the developing countries to borrow not only against the Fund,

but also against private banks which were receiving a surplus of OPEC

petrodollars, it was generally perceived at the time that the debt cads

would be short-lived. It was not until Mexico threatened to default on

its loans in 1982 that the world monetary community realized the extent

and depth of the crisis. Throughout the 1980s the Fund played an

increasingly larger role, not only as "lender-of-last-resort," but also

as mediator with debtor countries in relation to creditor nations and

private banks.

In the mid-1980s the Fund's lending operations increased dramatically.

Stand-by arrangements are typically for one to three years, but the

exigency of the debt crisis caused the Fund to devise programs for

adjustment over longer periods. These are known as extended arrangements

and, with other medium-term programs, can be arranged through the

Structural Adjustment Facility or the Enhanced Structural Adjustment

Facility. The terms of a structural adjustment program, or stabilization

program, are known as conditionality. Programs include quantified

targets or ceilings for bank credit, the budget deficit, foreign

borrowing, external arrears, and international reserves. They also

include statements of policies that the member intends to follow.

Conditionality came under detailed scrutiny during the 1980s as more and

more developing countries adopted structural adjustment programs and

later were unable to meet the terms of the agreement. The philosophy of

the Fund was criticized as being too oriented to the industrial

economies and not adapted to developing economies. During the late-1980s

several plans were put forth, involving not only the Fund but the

creditor nations and commercial banks as well, to reduce the debt and

the debt service payments of the debtor nations. In 1989 the Fund

developed new debt reduction guidelines, providing Fund support for

commercial bank debt and debt service-reduction operations by member

countries. The debt strategy is still being assessed and its success or

failure has not been determined."

Overview

Susan Aaronson of the National Policy Association also

provides a brief explanation of how the World Trade

Organization came into being:

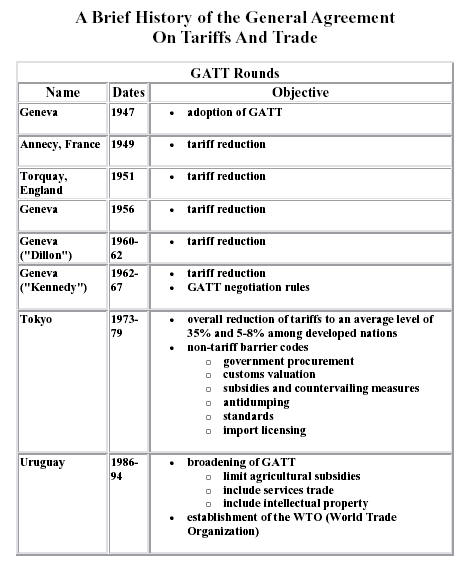

"The

Establishment of the WTO

By the late

1980s, a growing number of nations decided that GATT

could better serve global trade expansion if it became a

formal international organization. In 1988, the US

Congress, in the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act,

explicitly called for more effective dispute settlement

mechanisms. They pressed for negotiations to formalize

GATT and to make it a more powerful and comprehensive

organization. The result was the World Trade

Organization, (WTO), which was established during the

Uruguay Round (1986-1993) of GATT negotiations and which

subsumed GATT. The WTO provides a permanent arena for

member governments to address international trade issues

and it oversees the implementation of the trade

agreements negotiated in the Uruguay Round of trade

talks

The WTO's Powers

The WTO is

not simply GATT transformed into a formal international

organization. It covers a much broader purview,

including subsidies, intellectual property, food safety

and other policies that were once solely the subject of

national governments. The WTO also has strong dispute

settlement mechanisms. As under GATT, panels weigh trade

disputes, but these panels have to adhere to a strict

time schedule. Moreover, in contrast with GATT

procedure, no country can veto or delay panel decisions.

If US laws protecting the environment (such as laws

requiring gas mileage standards) were found to be de

facto trade impediments, the US must take action. It can

either change its law, do nothing and face retaliation,

or compensate the other party for lost trade if it keeps

such a law (Jackson, 1994).

The WTO's Mixed

Record

Despite its

broader scope and powers, the WTO has had a mixed

record. Nations have clamored to join this new

organization and receive the benefits of expanded trade

and formalized multinational rules. Today the WTO has

grown 142 members. Nations such as China, Russia, Saudi

Arabia and Ukraine hope to join the WTO soon. But since

the WTO was created, its members have not been able to

agree on the scope of a new round of trade talks. Many

developing countries believe that their industrialized

trading partners have not fully granted them the

benefits promised under the Uruguay Round of GATT. Some

countries regret including intellectual property

protections under the aegis of the WTO.

Protests

A wide range

of citizens has become concerned about the effect of

trade rules upon the achievement of other important

policy goals. In India, Latin America, Europe, Canada

and the United States, alarmed citizens have taken to

the streets to protest globalization and in particular

what they perceive as the undemocratic nature of the WTO.

During the fiftieth anniversary of GATT in Geneva in

1998, some 30,000 people rioted. During the Seattle

Ministerial Meetings in November/December 1999, again

about 30,000 people protested, some violently. "

GATT and the Environment:

As the text

observes, the word "environment" appears nowhere in the

language of GATT. However, this is not the major source of

concern for those concerned over the fate of the

environment. For many environmentalists, the premise of GATT

- "free trade" - is what is most troublesome, for they

consider the term to be completely antithetical to

environmental preservation and protection. There is also

concern that the the Uruguay Round of GATT will undercut the

autonomy of the U.S. to enforce its national environmental

laws - subjecting these laws to the higher authority of the

WTO. The Uruguay Round of GATT was dedicated to the

principle of "non-discrimination" in trade practices across

national boundaries.

Articles

I and III of GATT requires Contracting Parties

(Signatory nations) "to treat imports no less favorably than

other imports and no less favorably than similar domestic

goods after border duties." The Uruguay Round also

mandated that "contracting parties" adopt policies and

practices "necessary to protect human, animal or plant life

or health" that "relate to the conservation of exhaustible

natural resource." Likewise, in the spirit of Article

XX of GATT, nations must furthermore "arbitrary or

unjustifiable discrimination between countries" and national

trade policies must not be a "disguised restriction on

international trade."

The

"root of the trade-environment" conflict within GATT

revolves around three environmental "categories" that affect

trade:

(1) measures

aimed at reducing the comparative advantage

gained by lax environmental laws in a foreign nation;

(2) Measures

aimed at protecting the domestic environment;

and

(3) Measures

aimed at protecting global resources.

Although

environmental

laws inherently contain a wide range of social and policy

choices, few would advocate the use of a supranational body

to make these choices. Concerns have been raised that the

WTO may be dangerously close to becoming such a body; i.e.,

because of the intertwining of the environment and trade."

This raises the additional concern regarding the extent to

which "trade related decisions .. directed

towards environmental measures are necessarily making

national environmental policy choices."

Upon thoroughly

review the provisions of GATT, particularly those related to

non-discriminatory trade and policy behavior on the part of

participating parties, Parks concludes that:

"The WTO is

incapable of making national environmental policy

choices. Such choices should be left to national bodies,

or in the case of global issues, to the international

consensus building process. ... The WTO and the

principle of non-discrimination are fully capable of

setting the outer-limits of acceptable rules and

behavior as countries create their own environmental

laws to suit their particular cultural and sociological

needs. Furthermore, contrary to the concern raised about

the loss of sovereignty and environmental rights in the

WTO, the WTO will be able to protect legitimate

environmental laws that benefit the environment, while

shielding the world trading system from protectionist

laws (or portions of those laws) that have little to do

with environmental preservation.

However, other

policy analysts see other potential environmental issues

associated with GATT. For instance,

Courtney Harold and C. Ford Runge of the University of

Minnesota have identified three issues that are of

particular concern:

-

"The

potential impacts of trade liberalization on the

environment:

Increased environmental degradation may result

from an increased volume of trade, increased consumption

levels, increased demands on natural resources, and

increased levels of waste production and pollution.

There is also concern that international differences in

environmental standards will result in "havens" for

pollution for industries seeking to avoid strict

environmental regulations. Comparatively, there is

concern that international bodies like WTO may

ultimately promulgate environmental protection standards

that are less comprehensive than those embraced by many

nations, resulting in the dilution of international

environmental regulations to the "lowest common

denominator."

-

The

possible use of environmental measures as non-tariff

barriers to trade: The major concern in this

regard is nations or trading blocs will use the excuse

of environmental health and safety to stymie free trade.

The fundamental problem in this regard is to

discriminate between legitimate environmental health and

safety concerns from those that serve to block trade

while masquerading as "environmental" issues.

-

The

relationship between trade agreements under NAFTA (the

North American Free Trade Agreement) and GATT and the

variety of international agreements affecting the

environment, such as the Montreal Protocol. The

variety of modern trade agreements all contain unique

features relative to trade and the environment. At issue

is "how" to rationalize these disparate requirements and

"who" or "which body" will oversee and negotiate these

differences.

The concerns

raised by Harold and Runge are contextualize against two

"axes" (1) between the U.S. and the other major world

economies in Europe and Asia and the Pacific and (2) between

the so-called "North" and "South."

In fact, there

have been a

number of environmental disputes

over GATT (and later under the auspices of WTO) to

include: