Comparative

Advantage:

"Nobel

laureate Paul Samuelson (1969) was once challenged by the mathematician

Stanislaw Ulam to "name me one proposition in all of the social sciences

which is both true and non-trivial." It was several years later than he

thought of the correct response: comparative advantage. "That it is logically true need

not be argued before a mathematician; that is is not trivial is attested by

the thousands of important and intelligent men who have never been able to

grasp the doctrine for themselves or to believe it after it was explained to

them."

"What did David Ricardo mean when he coined

the term comparative advantage? According to the principle of comparative

advantage, the gains from trade follow from allowing an economy to

specialise. If a country is relatively better at making wine than

wool, it makes sense to put more resources into wine, and to export some of

the wine to pay for imports of wool. This is even true if that country is

the world's best wool producer, since the country will have more of both

wool and wine than it would have without trade. A country does not have to

be best at anything to gain from trade. The gains follow from specializing

in those activities which, at world prices, the country is relatively

better at, even though it may not have an absolute advantage in them.

Because it is relative advantage that matters, it is meaningless to say a

country has a comparative advantage in nothing. The term is one of the most

misunderstood ideas in economics, and is often wrongly assumed to mean an

absolute advantage compared with other countries."

"The

basis for trade in the Ricardian model is differences in technology

between countries. Below we define two different ways to describe technology

differences. The first method, called absolute advantage is the way most

people understand technology differences. The second method called

comparative advantage is a much more difficult concept. As a result even

those who learn about comparative advantage often will confuse it with

absolute advantage. It is quite common to see misapplications of the

principle of comparative advantage in newspaper and journal stories about

trade. Many times authors write comparative advantage when in actuality they

are describing absolute advantage. This misconception often leads to

erroneous implications such as a fear that technology advances in other

countries will cause our country to lose its comparative advantage in

everything. As will be shown, this is essentially impossible."

"Absolute Advantage: A country has an

absolute advantage in the production of a good relative to another

country if it can produce the good at lower cost or with higher

productivity. Absolute advantage compares industry productivities across

countries."

"Opportunity

Cost: Opportunity cost is defined generally as the value of

the next best opportunity. In the context of national production, the

nation has opportunities to produce wine and cheese. If the nation

wishes to produce more cheese, then because labor resources are scarce

and fully employed, it is necessary to move labor out of wine production

in order to increase cheese production. The loss in wine production

necessary to produce more cheese represents the opportunity cost to the

economy."

"

Comparative Advantage: A country has

a comparative advantage in the production of a good if it can produce

that good at a lower opportunity cost relative to another country.

"The

theory of comparative advantage is perhaps the most important concept in

international trade theory. It is also one of the most commonly

misunderstood principles." The sources of the misunderstandings are easy to

identify. First, the principle of comparative advantage is clearly

counter-intuitive. Many results from the formal model are contrary to simple

logic. Secondly, the theory is easy to confuse with another notion about

advantageous trade, known in trade theory as the theory of absolute

advantage. The logic behind absolute advantage is quite

intuitive. This confusion between these two concepts leads many people to

think that they understand comparative advantage when in fact, what they

understand, is absolute advantage. Finally, the theory of comparative

advantage is all too often presented only in its mathematical form. Using

numerical examples or diagrammatic representations are extremely useful in

demonstrating the basic results and the deeper implications of the theory.

However, it is also easy to see the results

mathematically, without ever understanding the basic intuition of the

theory.

The early logic that free trade could be

advantageous for countries was based on the concept of absolute advantages

in production. Adam Smith wrote in

The Wealth of Nations,

"If a foreign country can

supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better

buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry,

employed in a way in which we have some advantage. " (Book IV, Section

ii, 12)

The

idea here is simple and intuitive. If our country can produce some set of

goods at lower cost than a foreign country, and if the foreign country can

produce some other set of goods at a lower cost than we can produce them,

then clearly it would be best for us to trade our relatively cheaper goods

for their relatively cheaper goods. In this way both countries may gain from

trade.

The original idea of comparative advantage

dates to the early part of the 19th century. Although the model

describing the theory is commonly referred to as the "Ricardian model",

the original description of the idea

can be found in an

Essay on the External Corn Trade

by Robert Torrens in 1815. David Ricardo formalized the idea using a

compelling, yet simple, numerical example in his 1817 book titled,

On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

The idea appeared again in James Mill's

Elements of Political Economy

in 1821. Finally, the concept became a key feature of international

political economy upon the publication of

Principles of Political Economy

by John Stuart Mill in 1848.

David Ricardo's Assumptions

[Assumptions implicit within Ricardo's model are as follows:

The Ricardian model is

constructed such that the only difference between countries is in

their production technologies. All other features are assumed

identical across countries. Since trade would occur and be

advantageous, the model highlights one on the main reasons why

countries trade; namely, differences in technology.

Although most models of

trade suggest that some people would benefit and some lose from free

trade, the Ricardian model shows that everyone could benefit from

trade. This can be shown using an aggregate representation of

welfare (national indifference curves) or by calculating the change

in real wages to workers. However, one of the reasons for this

outcome is the simplifying assumption that there is only one factor

of production.

This interesting result

was first shown by Ricardo using a simple numerical example. The

analysis highlights the importance of producing a country's

comparative advantage good rather than its absolute advantage good.

The Ricardian model

shows the possibility that an industry in a developed country could

compete against an industry in a less developed country even though

the [competing] industry pays its workers much lower wages."

Comparative Advantage Illustration:

Here is a rather straightforward comparison of comparative advantage.

REMEMBER, comparative advantage means that a country should specialize in

trade that minimizes opportunity costs!

|

Comparative

Advantage Illustration

“David

Ricardo, working in the early part of the 19th century, realised

that absolute advantage was a limited case of a more general

theory. Consider Table 1. It can be seen that Portugal can

produce both wheat and wine more cheaply than England (ie it has

an absolute advantage in both commodities). What David Ricardo

saw was that it could still be mutually beneficial for both

countries to specialise and trade.

Table 1

|

Country |

Wheat |

Wine |

|

|

Cost Per Unit In Man Hours |

Cost Per Unit In Man Hours |

|

England |

15 |

30 |

|

Portugal |

10 |

15 |

In Table 1, a unit of wine in England costs the same amount to

produce as 2 units of wheat. Production of an extra unit of wine

means foregoing production of 2 units of wheat (ie the

opportunity cost of a unit of wine is 2 units of wheat). In

Portugal, a unit of wine costs 1.5 units of wheat to produce (ie

the opportunity cost of a unit of wine is 1.5 units of wheat in

Portugal). Because relative or comparative costs differ, it will

still be mutually advantageous for both countries to trade even

though Portugal has an absolute advantage in both commodities.

Portugal is relatively better at producing wine than wheat: so

Portugal is said to have a COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE in the

production of wine. England is relatively better at producing

wheat than wine: so England is said to have a comparative

advantage in the production of wheat.

Table 2 shows how trade might be advantageous. Costs of

production are as set out in Table 1. England is assumed to have

270 man hours available for production. Before trade takes place

it produces and consumes 8 units of wheat and 5 units of wine.

Portugal has fewer labour resources with 180 man hours of labour

available for production. Before trade takes place it produces

and consumes 9 units of wheat and 6 units of wine. Total

production between the two economies is 17 units of wheat and 11

units of wine.

Table 2

|

C o u n t r y |

Production |

|

Before Trade |

After Trade |

|

Wheat |

Wine |

Wheat |

Wine |

|

E n g l a n d |

8 |

5 |

18 |

0 |

|

P o r t u g a l |

9 |

6 |

0 |

12 |

|

T o t a l |

17 |

11 |

18 |

12 |

If both countries now specialise, Portugal producing only wine

and England producing only wheat, total production is 18 units

of wheat and 12 units of wine. Specialisation has enabled the

world economy to increase production by 1 unit of wheat and 1

unit of wine.

The simple theory of comparative advantage outlined above makes

a number of important assumptions:

|

"A

country is said to have a comparative advantage in the production of a good

(say cloth) if it can produce cloth at a lower opportunity cost than another

country. The opportunity cost of cloth production is defined as the amount

of wine that must be given up in order to produce one more unit of cloth.

Thus England would have the comparative advantage in cloth production

relative to Portugal if it must give up less wine to produce another unit of

cloth than the amount of wine that Portugal would have to give up to produce

another unit of cloth.

All

in all, this condition is rather confusing. Suffice it to say, that it is

quite possible, indeed likely, that although England may be less productive

in producing both goods relative to Portugal, it will nonetheless have a

comparative advantage in the production of one of the two goods. Indeed

there is only one circumstance in which England would not have a comparative

advantage in either good, and in this case Portugal also would not have a

comparative advantage in either good. In other words, either each country

has the comparative advantage in one of the two goods or neither country has

a comparative advantage in anything.

Another way to define comparative advantage

is by comparing productivities across industries and countries. Thus

suppose, as before, that Portugal is more productive than England in the

production of both cloth and wine. If Portugal is twice as productive in

cloth production relative to England but three times as productive in wine,

then Portugal's comparative advantage is in wine, the good in which its

productivity advantage is greatest. Similarly, England's comparative

advantage good is cloth, the good in which its productivity disadvantage is

least. This implies that to

benefit from specialization and free trade, Portugal should specialize and

trade the good in which it is "most best" at producing, while England should

specialize and trade the good in which it is "least worse" at

producing.

Note that trade based on comparative does not contradict Adam Smith's notion

of advantageous trade based on absolute advantage. If as in Smith's example,

England were more productive in cloth production and Portugal were more

productive in wine, then by we would say that England has an absolute

advantage in cloth production while Portugal has an absolute advantage in

wine. If we calculated comparative advantages, then England would also have

the comparative advantage in cloth and Portugal would have the comparative

advantage in wine. In this case, gains from trade could be realized if both

countries specialized in their comparative, and absolute, advantage goods.

Advantageous trade based on comparative advantage, then, covers a larger set

of circumstances while still including the case of absolute advantage and

hence is a more general theory."

Economies of Scale:

Another concept related to "comparative advantage" is the concept of

"economies of scale." Economies of scale can be conceptualized in the

following way. "When more units of a good or a service can be produced on a

larger scale, yet with (on average) less input costs, economies of scale

(ES) are said to be achieved. Alternatively, this means that as a company

grows and production units increase, a company will have a better chance to

decrease its costs. According to theory, economic growth may be achieved

when economies of scale are realized.

Adam Smith identified the division of labor and specialization as the two

key means to achieve a larger return on production. Through these two

techniques, employees would not only be able to concentrate on a specific

task, but with time, improve the skills necessary to perform their jobs. The

tasks could then be performed better and faster. Hence, through such

efficiency, time and money could be saved while production levels

increased."

"Just like there are economies of scale, diseconomies of scale (DS) also

exist. This occurs when production is less than in proportion to inputs.

What this means is that there are inefficiencies within the firm or industry

resulting in rising average costs."

"Alfred Marshall made a distinction between internal and external economies

of scale. When a company reduces costs and increases production, internal

economies of scale have been achieved. External economies of scale occur

outside of a firm, within an industry. Thus, when an industry's scope of

operations expands due to, for example, the creation of a better

transportation network, resulting in a subsequent decrease in cost for a

company working within that industry, external economies of scale are said

to have been achieved. With external ES, all firms within the industry will

benefit."

The "Liberalized Trade"

Philosophy

Authors of the text Environmental Law & Policy (Salzman & Thompson, 2003)

are critical of "liberalized trade" (which is to say global free trade)

fearing that it will result in the overuse of natural resources, the

creation of excessive and unnecessary waste, and the ultimate weakening of

environmental standards. An alternative perspective is presented by the

Washington Business Roundtable:

"An honest and intelligent

debate about the impact of trade and investment liberalization on the

United States requires the separation of fact from fiction.

MYTH: Liberalization

undermines environmental protection laws and harms the environment.

TRUTH:

-

Trade agreements do

not dictate U.S. environmental law or undermine U.S.

environmental laws. International trade agreements require the

United States only to apply the same standards to imported

products that it applies to domestic products. Trade agreements

do not prevent other countries from applying the same

environmental standards to U.S. goods that they apply to their

own goods.

-

To achieve

environmental sustainability, countries need good environmental

laws and effective enforcement of those laws. Liberalized trade

produces higher incomes and economic growth that make it

possible for countries to improve their environmental laws and

law enforcement.

-

The U.S.-Singapore

and U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreements require the governments of

the United States, Chile and Singapore to (1) effectively

enforce environmental laws, (2) ensure that they do not weaken

their environmental laws to encourage trade or investment, and

(3) ensure that violations of their respective environmental

laws are subject to sanctions by legal procedure.

-

Liberalized trade

helps improve environmental protection by lowering the barriers

to the sale of environmental technologies; enabling new

investments in environmental infrastructure; and making it

easier for environmental scientists, engineers and technicians

to provide services to developing countries.

MYTH: Liberalization

undermines protection for labor.

TRUTH:

-

Trade agreements do

not require the United States to change its labor laws or

undermine U.S. laws protecting labor rights.

-

Trade liberalization

does not undermine worker rights. In fact, the opposite is true.

In a study of 44 developing countries that engaged in

significant trade liberalization, the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that “there was

notably no case where the trade reforms were followed by a

worsening of association rights” and that freedom-of-association

rights improved in 32 of the countries after trade

liberalization.

-

The U.S.-Singapore

and U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreements require the governments of

the United States, Chile and Singapore to (1) effectively

enforce labor laws, (2) work to ensure that International Labor

Organization (ILO) principles are protected by their domestic

laws, (3) ensure that they do not weaken their labor laws to

encourage trade or investment, and (4) ensure that legal

proceedings are available to sanction violations of labor laws.

MYTH: Trade

agreements undermine U.S. sovereignty by giving international

bureaucrats the power to strike down U.S. laws.

TRUTH:

-

Only the U.S.

Congress and the U.S. president can make U.S. law, no

international institution or foreign country can change U.S.

laws.

-

Decisions by the

World Trade Organization (WTO) and the North American Free Trade

Agreement (NAFTA) dispute panels cannot override U.S. law. Those

panels can only issue recommendations, and these recommendations

have no force in the United States. Only the Congress and the

president can decide whether to implement a panel

recommendation. They can (1) revise U.S. law, (2) compensate a

country harmed by a U.S. law through reductions in tariffs or

other trade barriers, or (3) do nothing — and accept the risk

that the other country may retaliate by raising tariffs or other

barriers to U.S. exports.

-

The United States

may withdraw from the WTO, NAFTA, free trade agreements and all

other trade agreements at any time.

MYTH: Trade

liberalization increases U.S. trade deficits.

TRUTH:

-

The United States

had trade deficits before the WTO existed and would have them if

there were no WTO. The merchandise trade deficit generally grows

when the economy grows and shrinks when the economy shrinks.

-

The trade deficit is

a result of American prosperity. The strength of the U.S.

economy means U.S. consumers are able to purchase a wide variety

of goods and services, including imports.

-

Imports help keep

inflation low by ensuring that U.S. consumers have access to a

variety of competitively priced goods and that producers have

access to low-cost inputs.

MYTH: Trade

liberalization causes good U.S. jobs to move overseas.

TRUTH:

-

Trade creates good

jobs in the United States. Ten percent of all U.S. jobs

(approximately 12 million) depend on exports. One in five

factory jobs depend on international trade. Jobs that depend on

trade generally pay about 13 to 18 percent more than the average

U.S. wage.

-

U.S. plants that

export increase employment 2 to 4 percent faster annually

compared to plants that do not export. Exporting plants also are

less likely to go out of business.

-

U.S. firms that are

deeply integrated in worldwide markets are more likely to

succeed in generating good jobs at home. Such jobs pay an

average wage in the United States of $15,000 more than jobs in

firms that are less globally integrated, or $50,000 versus

$35,000.

-

Contrary to the

predictions of a “giant sucking sound,” NAFTA has created good

jobs in the United States. In the first eight years of NAFTA,

the number of U.S. jobs supported by merchandise exports to

Mexico and Canada grew from 914,000 to 2.9 million. Between 1993

and 2000, U.S. employment grew by 20 million. Real hourly

compensation in the U.S. manufacturing sector increased by 14.4

percent in the 10 years following NAFTA implementation, as

compared to 6.5 percent in the 10 years prior to NAFTA."

"Race to the Bottom"

According to the World Bank in its report entitled "Is

Globalization Causing a 'Race To The Bottom' in Environmental Standards?"

(part four of a set of

World Bank briefing papers on this topic) the concern regarding a "race to the

bottom" resulting from lax environmental standards produced by free global

trade is unfounded. The authors of this report present their position as

follows:

"It

is argued that increased international competition for investment will

cause countries to lower environmental regulations (or to retain poor

ones), a “race to the bottom” in environmental standards as countries

fight to attract foreign capital and keep domestic investment at home.

However there is no evidence that the cost of environmental protection

has ever been the determining factor in foreign investment decisions.

Factors such as

labor and raw material costs, transparent regulation and protection of

property rights are likely to be much more important, even for polluting

industries. Indeed, foreign-owned plants in developing countries,

precisely the ones that according to the theory would be most attracted

by low standards, tend to be less polluting than indigenous plants in

the same industry. Most multinational companies adopt near-uniform

standards globally, often well above the local government-set standards

. This suggests that they relocate plants to developing countries for

reasons other than low environmental standards. Paradoxically, pollution

[as] an effect may be more important within the national boundaries of a

developed country than between rich and poor countries. Within a

national boundary many of the other locational factors are less

important, and so local environmental regulations might matter more."

"Countries

do not become permanent pollution havens because along with increases in

income come increased demands for environmental quality and a better

institutional capacity to supply environmental regulation. One World

Bank study of 145 countries identified a strong positive correlation

between income levels and the strictness of environmental regulation.

Indeed the so-called "California Effect" in the US demonstrates that

there is nothing inevitable about a ‘race to the bottom. After the

passage of the US 1970 Clean Air Act Amendments, California repeatedly

adopted stricter emissions standards than other US states. Instead of a

flight of investment and jobs from California, however, other states

began adopting similar, tougher emissions standards. A self-reinforcing

“race to the top" was thus put in place in which California helped lift

standards throughout the US.

[Some researchers

attribute this phenomenon] to the "lure of green markets" - car manufacturers were

willing to meet California's higher standards to avoid

losing such a large market and once they had met the standard in one

state, they could easily meet it in every state."

The

World Bank also attributes the penchant for some to associate a "race

to the bottom" mentality with a general (and widespread)

misunderstanding of what is entailed with globalization. Accordingly, the

World Bank describes "Globalization"

in the following fashion:

"Globalization is one of the most charged issues of the day. It is

everywhere in public discourse – in TV sound bites and slogans on

placards, in web-sites and learned journals, in parliaments, corporate

boardrooms and labor meeting halls. Extreme opponents charge it with

impoverishing the world's poor, enriching the rich and devastating the

environment, while fervent supporters see it as a high-speed elevator to

universal peace and prosperity. What is one to think?

Amazingly for so widely used

a term, there does not appear to be any precise, widely-agreed

definition. Indeed the breadth of meanings attached to it seems to be

increasing rather than narrowing over time, taking on cultural,

political and other connotations in addition to the economic. However,

the most common or core sense of economic globalization surely

refers to the observation that in recent years a quickly rising share of

economic activity in the world seems to be taking place between people

who live in different countries (rather than in the same country). This

growth in cross-border economic activities takes various forms:

International

Trade:

A growing share of spending on goods and services is devoted to

imports from other countries. And a growing share of what countries

produce is sold to foreigners as exports. Among rich or developed

countries the share of international trade in total output (exports

plus imports of goods relative to GDP) rose from 27 to 39 percent

between 1987 and 1997. For developing countries it rose from 10 to

17 percent. (The source for many of these data is the World Bank's

World Development Indicators 2000.)

Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI).

Firms based in one country increasingly make investments to

establish and run business operations in other countries. US firms

invested US$133 billion abroad in 1998, while foreign firms invested

US$193 billion in the US. Overall world FDI flows more than tripled

between 1988 and 1998, from US$192 billion to US$610 billion, and

the share of FDI to GDP is generally rising in both developed and

developing countries. Developing countries received about a quarter

of world FDI inflows in 1988-98 on average, though the share

fluctuated quite a bit from year to year. This is now the largest

form of private capital inflow to developing countries.

Capital Market

Flows.

In many countries (especially in the developed world) savers

increasingly diversify their portfolios to include foreign financial

assets (foreign bonds, equities, loans), while borrowers

increasingly turn to foreign sources of funds, along with domestic

ones. While flows of this kind to developing countries also rose

sharply in the 1990s, they have been much more volatile than either

trade or FDI flows, and have also been restricted to a narrower

range of 'emerging market' countries.

Overall Observations

about Globalization:

First, it is crucial in discussing globalization to

carefully distinguish between its different forms.

International trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), and capital market

flows raise distinct issues and have distinct consequences: potential

benefits on the one hand, and costs or risks on the other, calling for

different assessments and policy responses. The World Bank generally

favors greater openness to trade and FDI because the evidence suggests

that the payoffs for economic development and poverty reduction tend to

be large relative to potential costs or risks (while also paying

attention to specific policies to mitigate or alleviate these costs and

risks).

It is more cautious about

liberalization of other financial or capital market flows, whose high

volatility can sometimes foster boom-and-bust cycles and financial

crises with large economic costs, as in the emerging-market crises in

East Asia and elsewhere in 1997-98. Here the emphasis needs to be more

on building up supportive domestic institutions and policies that reduce

the risks of financial crisis before undertaking an orderly and

carefully sequenced capital account opening.

Second, the extent to

which different countries participate in globalization is also far from

uniform.

For many of the poorest least-developed countries the problem is not

that they are being impoverished by globalization, but that they are in

danger of being largely excluded from it. The minuscule 0.4 percent

share of these countries in world trade in 1997 was down by half from

1980. Their access to foreign private investment remains negligible. Far

from condemning these countries to continued isolation and poverty, the

urgent task of the international community is to help them become better

integrated in the world economy, providing assistance to help them build

up needed supporting institutions and policies, as well as by continuing

to enhance their access to world markets.

Third, it is important to

recognize that economic globalization is not a wholly new trend.

Indeed, at a basic level, it has been an aspect of the human story from

earliest times, as widely scattered populations gradually became

involved in more extensive and complicated economic relations. In the

modern era, globalization saw an earlier flowering towards the end of

the 19th century, mainly among the countries that are today developed or

rich. For many of these countries trade and capital market flows

relative to GDP were close to or higher than in recent years. That

earlier peak of globalization was reversed in the first half of the 20th

century, a time of growing protectionism, in a context of bitter

national and great-power strife, world wars, revolutions, rising

authoritarian ideologies, and massive economic and political

instability.

In the last 50 years the

tide has flown towards greater globalization once more. International

relations have been more tranquil (at least compared to the previous

half century), supported by the creation and consolidation of the United

Nations system as a means of peacefully resolving political differences

between states, and of institutions like the GATT (today the WTO), which

provide a framework of rules for countries to manage their commercial

policies. The end of colonialism brought scores of independent new

actors onto the world scene, while also removing a shameful stain

associated with the earlier 19th century episode of globalization. The

1994 Uruguay Round of the GATT saw developing countries become engaged

on a wide range of multilateral international trade issues for the first

time.

The pace of international

economic integration accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s, as governments

everywhere reduced policy barriers that hampered international trade and

investment.

Opening to the outside world has been part of a more general shift

towards greater reliance on markets and private enterprise, especially

as many developing and communist countries came to see that high levels

of government planning and intervention were failing to deliver the

desired development outcomes.

China's sweeping economic

reforms since the end of the 1970s, the peaceful dissolution of

communism in the Soviet bloc at the end of the 1980s, and the taking

root and steady growth of market based reforms in democratic India in

the 1990s are among the most striking examples of this trend.

Globalization has also been fostered by technological progress, which is

reducing the costs of transportation and communications between

countries. Dramatic falls in the cost of telecommunications, of

processing, storing and transmitting information, make it much easier to

track down and close on business opportunities around the world, to

coordinate operations in far-flung locations, or to trade online

services that previously were not internationally tradable at all.

Finally, given this

backdrop, it may not be surprising (though it is not very helpful) that

'globalization' is sometimes used in a much broader economic sense, as

another name for capitalism or the market economy.

When used in this sense the concerns expressed are really about key

features of the market economy, such as production by privately-owned

and profit-motivated corporations, frequent reshuffling of resources

according to changes in supply and demand, and unpredictable and rapid

technological change. It is certainly important to analyze the strengths

and weaknesses of the market economy as such, and to better understand

the institutions and policies needed to make it work most effectively.

And societies need to think hard about how to best manage the

implications of rapid technological change. But there is little to be

gained by confusing these distinct (though related) issues with economic

globalization in its core sense, that is the expansion of cross-border

economic ties.

Conclusion.

The best way to deal with the changes being brought about by the

international integration of markets for goods, services and capital is

to be open and honest about them. As this series of Briefs note,

globalization brings opportunities, but it also brings risks. While

exploiting the opportunities for higher economic growth and better

living standards that more openness brings, policy makers -

international, national and local – also face the challenge of

mitigating the risks for the poor, vulnerable and marginalized, and of

increasing equity and inclusion.

Even when poverty is falling

overall, there can be regional or sectoral increases about which society

needs to be concerned. Over the last century the forces of globalization

have been among those that have contributed to a huge improvement in

human welfare, including raising countless millions out of poverty.

Going forward, these forces have the potential to continue bringing

great benefits to the poor, but how strongly they do so will also

continue to depend crucially on factors such as the quality of overall

macroeconomic policies, the workings of institutions, both formal and

informal, the existing structure of assets, and the available resources,

among many others. In order to arrive at fair and workable approaches to

these very real human needs, government must listen to the voices of all

its citizens."

Traditional

versus Sustainable Economics:

Many

policy analysts (such as Salzman and Thompson) are not impressed by the

arguments of the World Bank and are troubled by the increasing orientation

of the world economy toward "liberalization" and

"globalization." Their concerns are primarily based upon their

pessismism regarding the future of so-called "conventional"

economic models that, among other things, does not routinely include the

replacement costs for natural resources or a full accounting of

"waste" production into their economic models. These analysts tend

to argue for the replacement of "conventional,"

"traditional" or "capitalist" models with what they call

"sustainable economies."

According

to the Center

of Economic Conversion economics can be conceptualized in a variety of

ways. For instance, "Subsistence economies, which prevail

in the more remote and less industrialized areas of the world, place much

value on ecology and living in harmony within the natural limits of

their environment. Capitalist and Socialist economies both share the goal of

generating material wealth but differ in their approach. Capitalist

economies emphasize individual freedom while Socialist

economies emphasize social equality. The Buddhist

economic system, as described by E.F. Schumacher and lived by

some Eastern countries, is centered on the goal of human fulfillment

and the development of character."

In

the interest of understanding what is meant by the ideal of a

"sustainable economy" Daniel

O'Connor, in his article

"Sustainable

Growth: Irreconcilable Visions?" published on the web-based

Economics Roundtable,

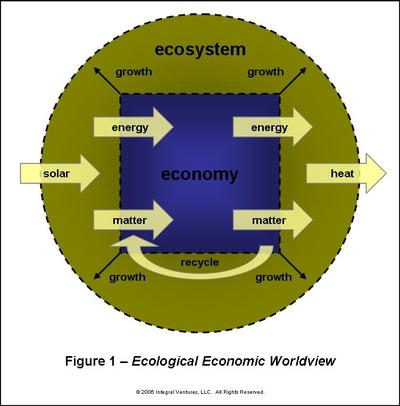

presents two separate visions of economic systems. In the first system (see

illustration below)

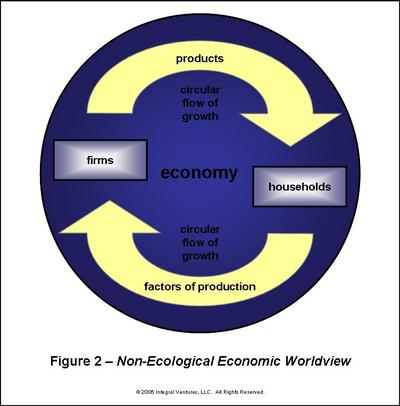

O'Donnell

conceptualizes an ecological economic system as one whose growth is

contained and limited by the resources of the ecosystem. By comparison, a

classical economic system (such as the one depicted below) operates as if

there are no ecological constraints to growth.

Such

classical formulations of economics would appear to be unrealistic given

what appears to be the inherent finite nature of natural resources.

Consequently, based upon this comparison, a sustainable economy could be

defined (as it has been by the Ecosystem

Health program at the University

of Western Ontario) as an "Economic system in which the number of

people and the quantity of goods are maintained at some constant level. This

level is ecologically sustainable over time and meets at least the basic

needs of all members of the population."

Sustainable

economies are by definition more complex that traditional economic models as

they attend to a variety of indicators beyond those "growth"

oriented indicators narrowly associated with supply and demand. The table

below makes a cogent presentation of these economic indicators and how

"traditional" and "sustainable" economic models construe

each indicator:

Clearly,

the move toward a "sustainable" economic model entails much more

complexity and government involvement in regulatory affairs, both

economically as well as socially and environmentally. The prospects of

such a model being widely adopted, while heralded by many as necessary for

the survival of human beings on the planet, is also decried by others. For

an interesting alternative opinion on the merits of sustainable economies

read Jacqueline

R. Kasun's thoughtful article "Doomsday

Everyday: Sustainable Economics, Sustainable Tyranny."

Return to the Top of the Page |